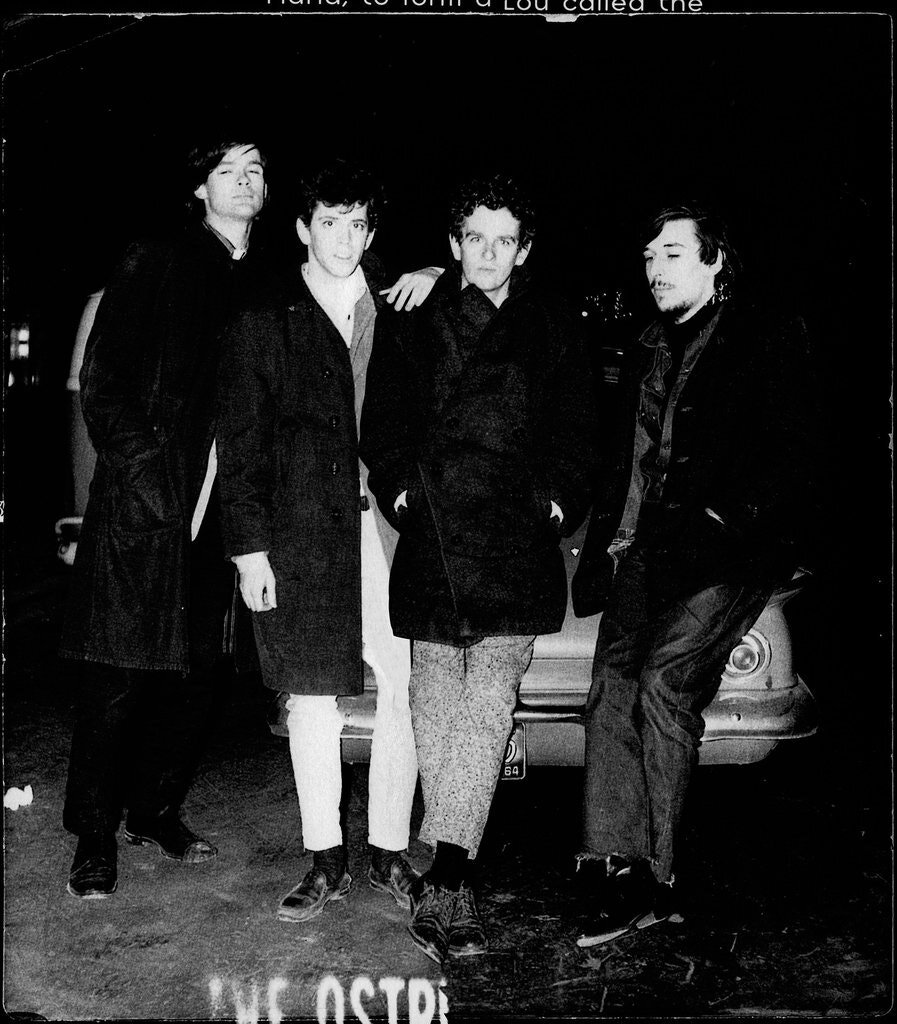

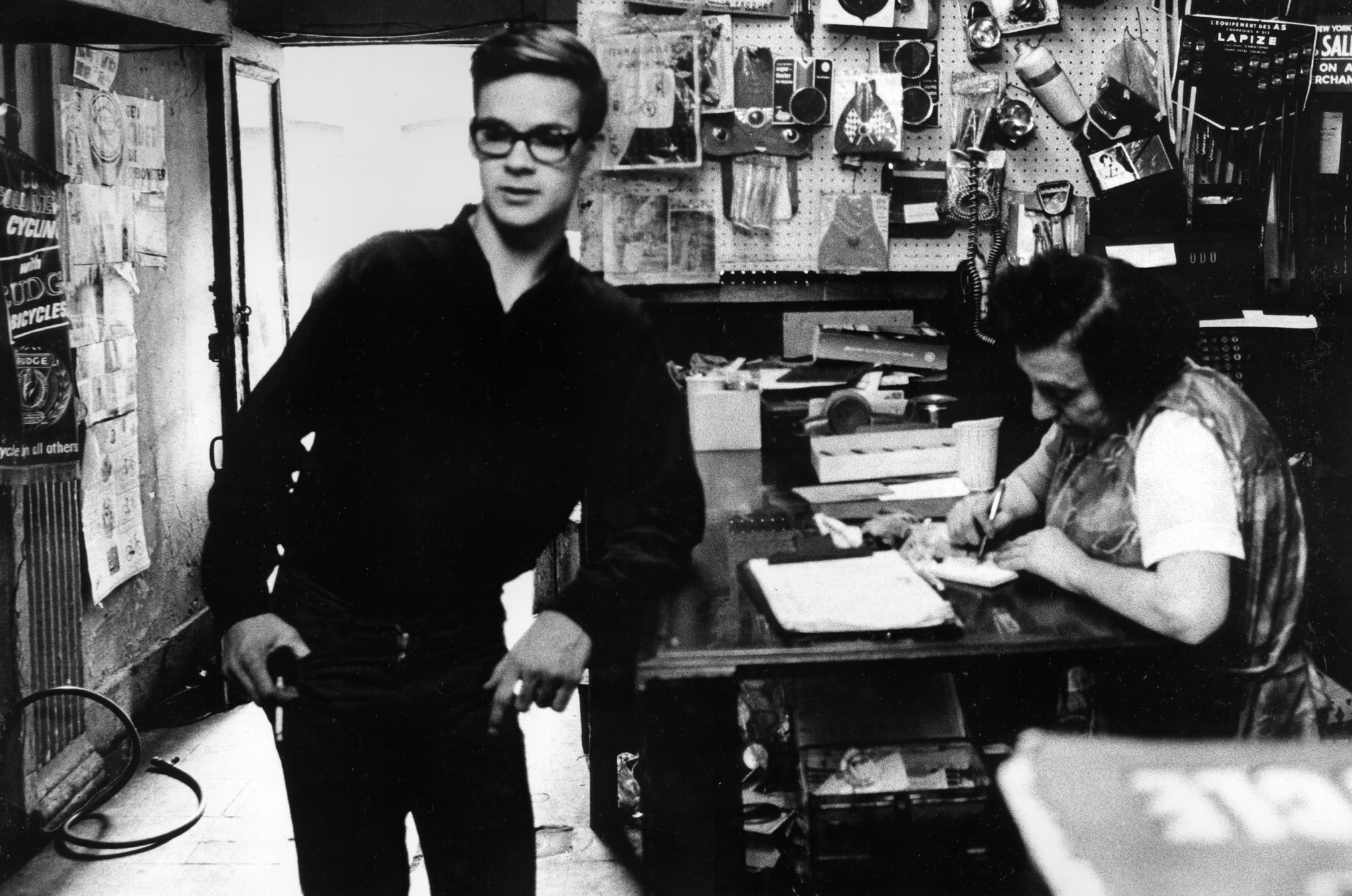

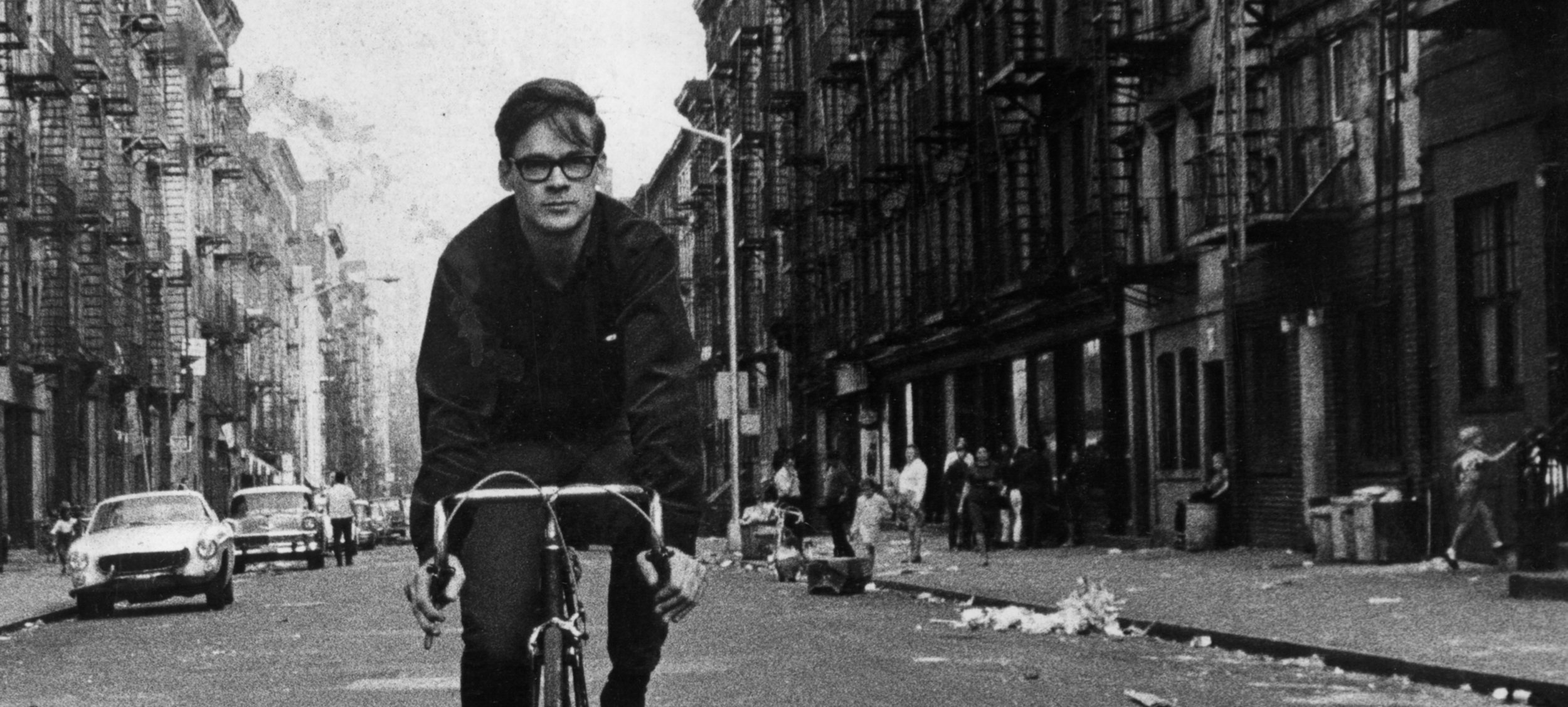

The Primitives, a precursor to the Velvet Underground, in 1965. From left, Mr. Conrad, Lou Reed, Walter DeMaria and John Cale. Credit...via Tyler Hubby

"People like Conrad, so free of many of the conventional ideas and restraints that often just end up being selling points, reminds me that as down as you want to feel is just how much you want to deny the fact that there have been brilliant people in every decade, including this one, pushing in every possible way against mediocrity, conformity and ignorance. When in doubt, go to the museum, the gallery, the record store, anywhere you can find art. The world might not change, but yours could."

Henry Rollins, LA Weekly

“They mixed it too soft and made me sound like a hippie.”

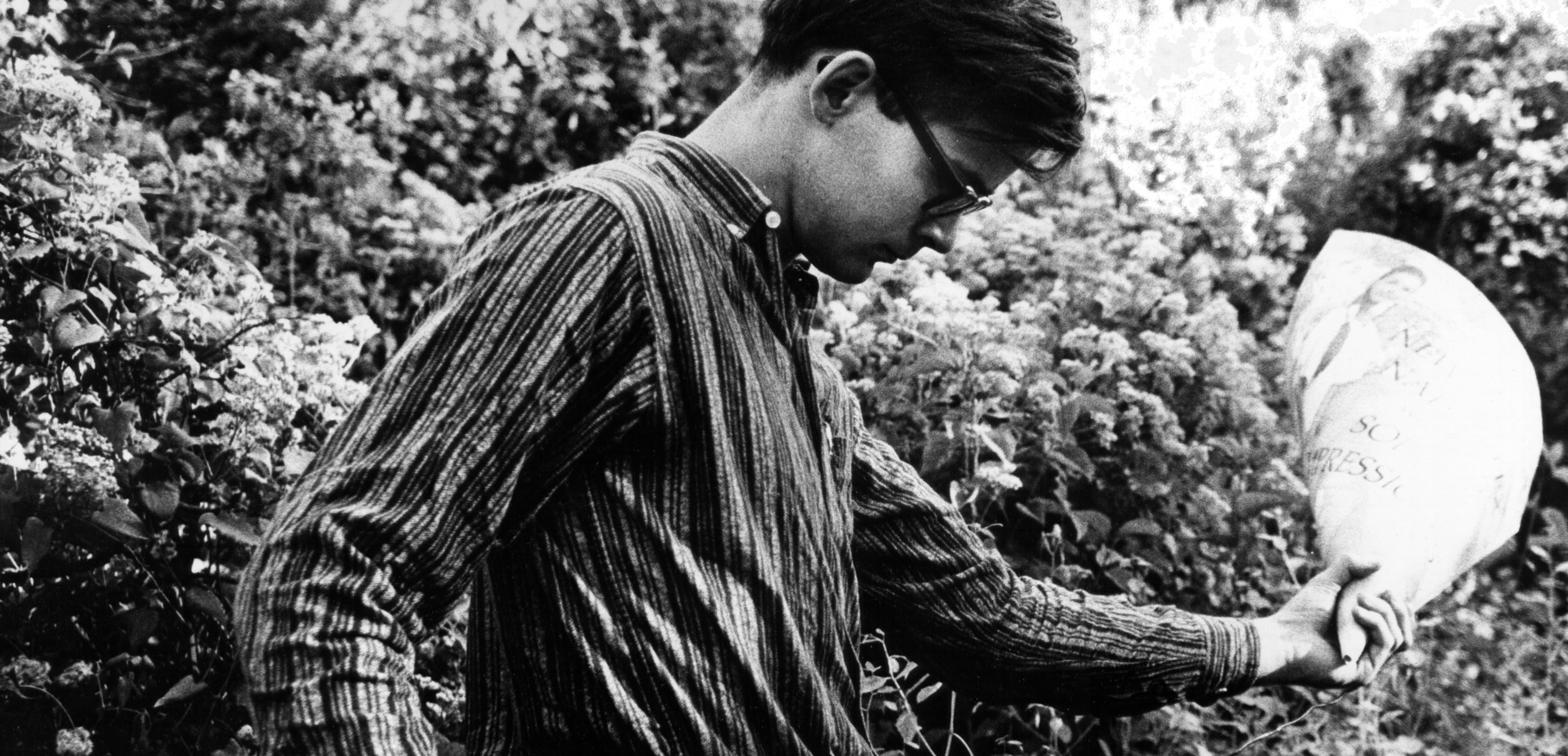

Original photobooth image, 1965. This image ©Table of the Elements Archive

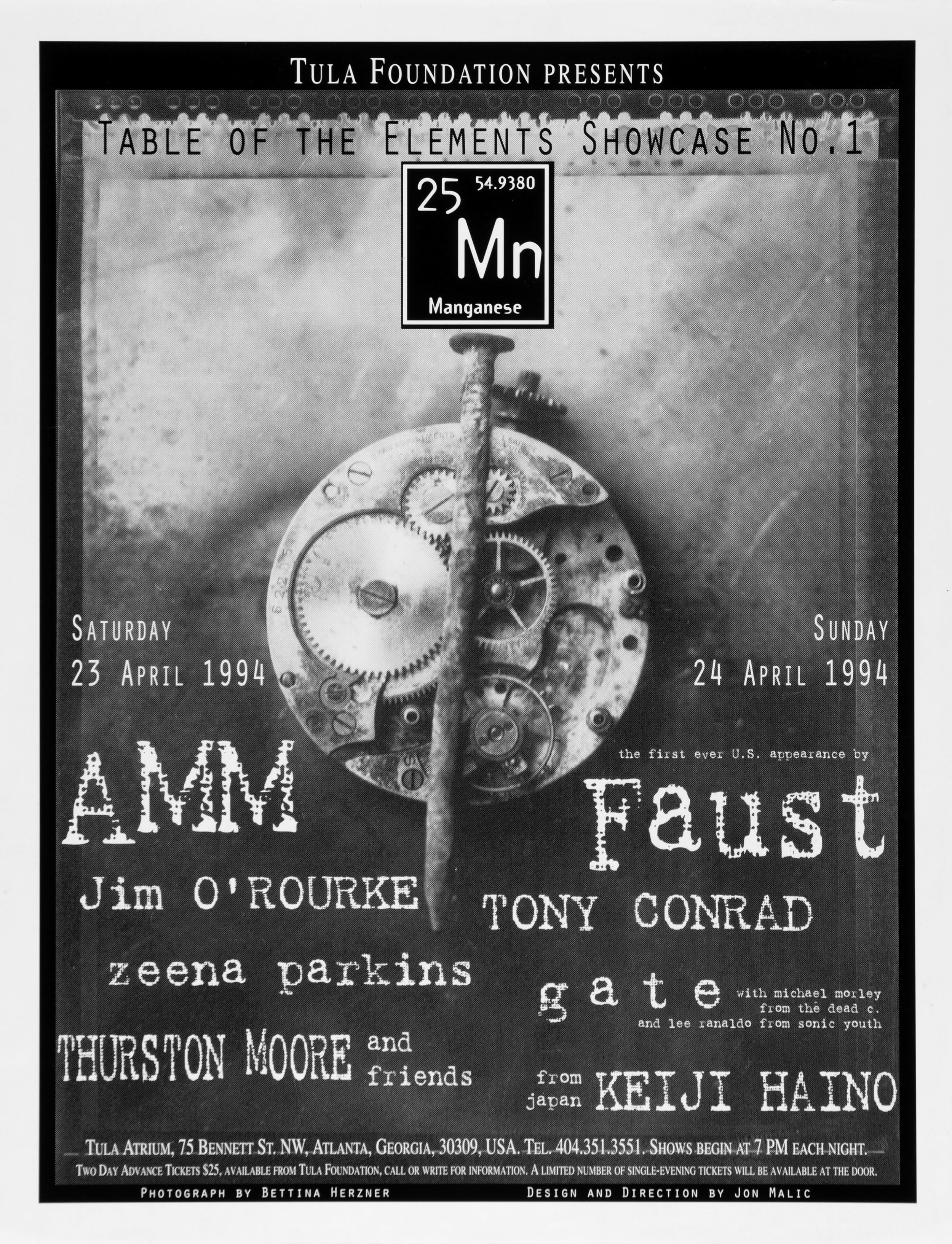

Tony Conrad with Faust

Outside the Dream Syndicate

1993

Table of the Elements

[Lithium] TOE-CD-3

Compact disc

Tony Conrad with Faust

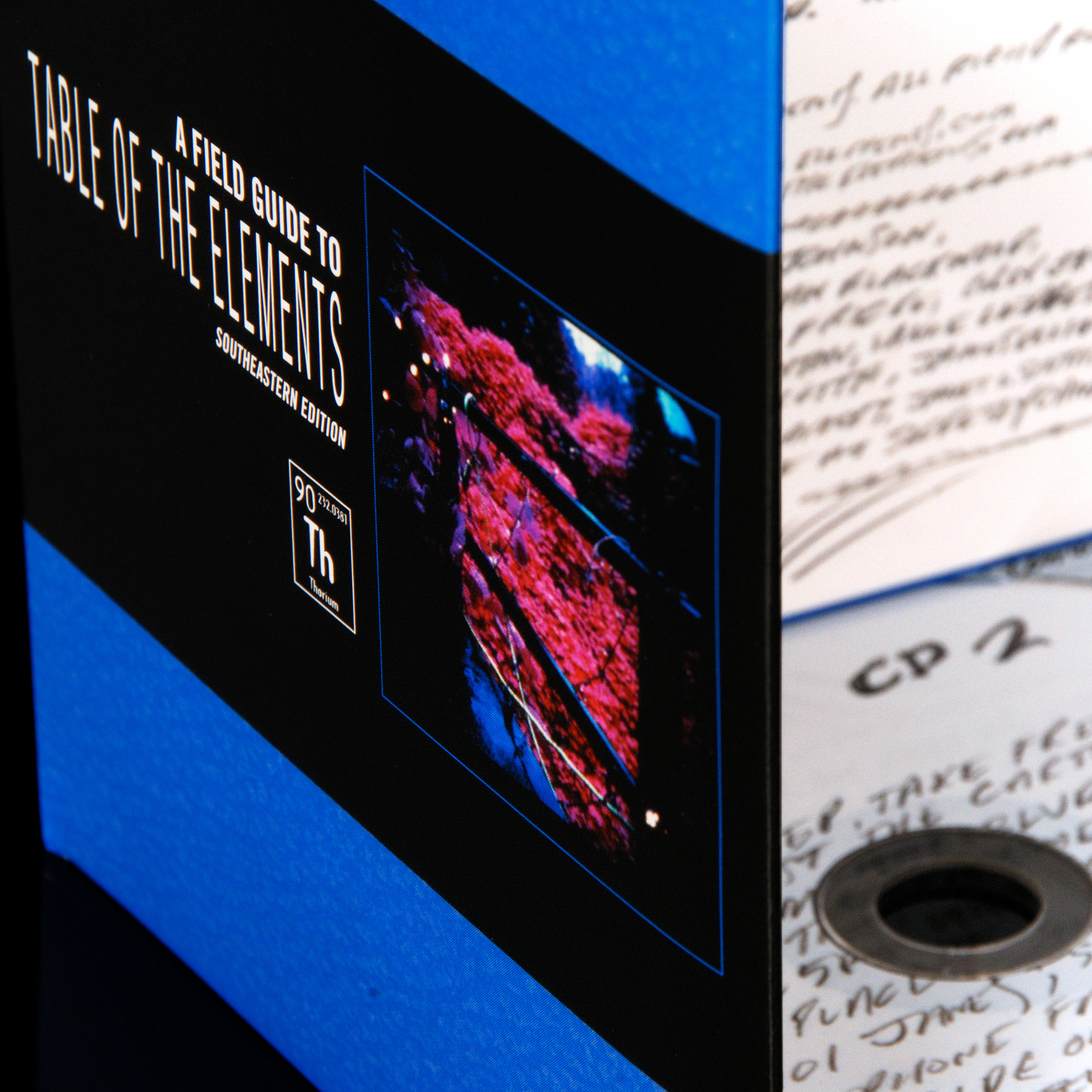

Outside the Dream Syndicate: 10th Anniversary Edition Box

2002

Table of the Elements

[Lithium] SWC-CD-302

2x compact discs, poster, sticker, 16-page book, 96-page catalog, foil stamp, enclosure

Tony Conrad with Faust

Outside the Dream Syndicate: 10th Anniversary Edition

2004

Table of the Elements

[Lithium] SWC-CD-302

2x compact discs sticker, 16-page book, foil stamp

Double CD in deluxe, limited-edition packaging

Includes unreleased material from the original 1972 sessions

Digitally remastered for this release

Features new liner notes by Rolling Stone senior editor David Fricke

"Out-machines Metal Machine Music."

Creem

"Whether you heard it in 1972, or in the present time, it still kicks infinitely. At its most basic, this an early fusion of the classical and avant-garde with the more rock and pop sensibilities of the day, something not seen since the Beatles' Stockhausen riff, 'Revolution #9,'and scarcely since. It couples minimal tones with an almost James Brown-like bass-kick bottom and relentless thrust. The results are prodigious, prophetic, powerful. To this day there's still nothing quite like its primitive, otherworldly chug ... Together [Conrad and Faust] elevate into endless crescendos and cascades of holy sound, floating on an Om-like soundwave. Whether an initiate or a first-timer, this is something quite timeless."

Andy Beta, Luna Kafe

"Conrad invents a new musical language ... unbearably intense and gloriously ecstatic."

The Wire

"A terribly exciting, endlessly fascinating genre-bender ... absolutely exhilarating."

The Yale Herald

"Behold the glacier with an amplified pulse!"

Tower Pulse

"Monumental ... Just follow your bliss."

Philadelphia Weekly

"Top-5 Reissues of 2002."

Washington City Paper

"Top-10 Reissues of 2002."

The Wire

An old Zen koan comes to mind; delivered through the lesser hands of seekers and compilers, beats and Deadheads, the New Age-- but surely, I imagine, of wise and noble provenance somewhere back. A flag flapping in the gale sparks an argument between two monks on the nature of things. The first declares that the flag is surely moving. The flag is still, counters the other, it is the wind that is moving. Sure enough, where an insoluble paradox appears, the wandering master is not far behind. Which is it, ask the monks, is the flag moving or is the wind moving? Neither, replies the master; mind is moving.

Fair enough. Take it, like any wisdom, with a grain of salt, but it springs to mind. Not because Tony Conrad sees still air and a flapping flag, or because Faust occupy a world of volatile weather, but just because, for a moment in Outside the Dream Syndicate, one forgets what exactly is moving and what is standing still.

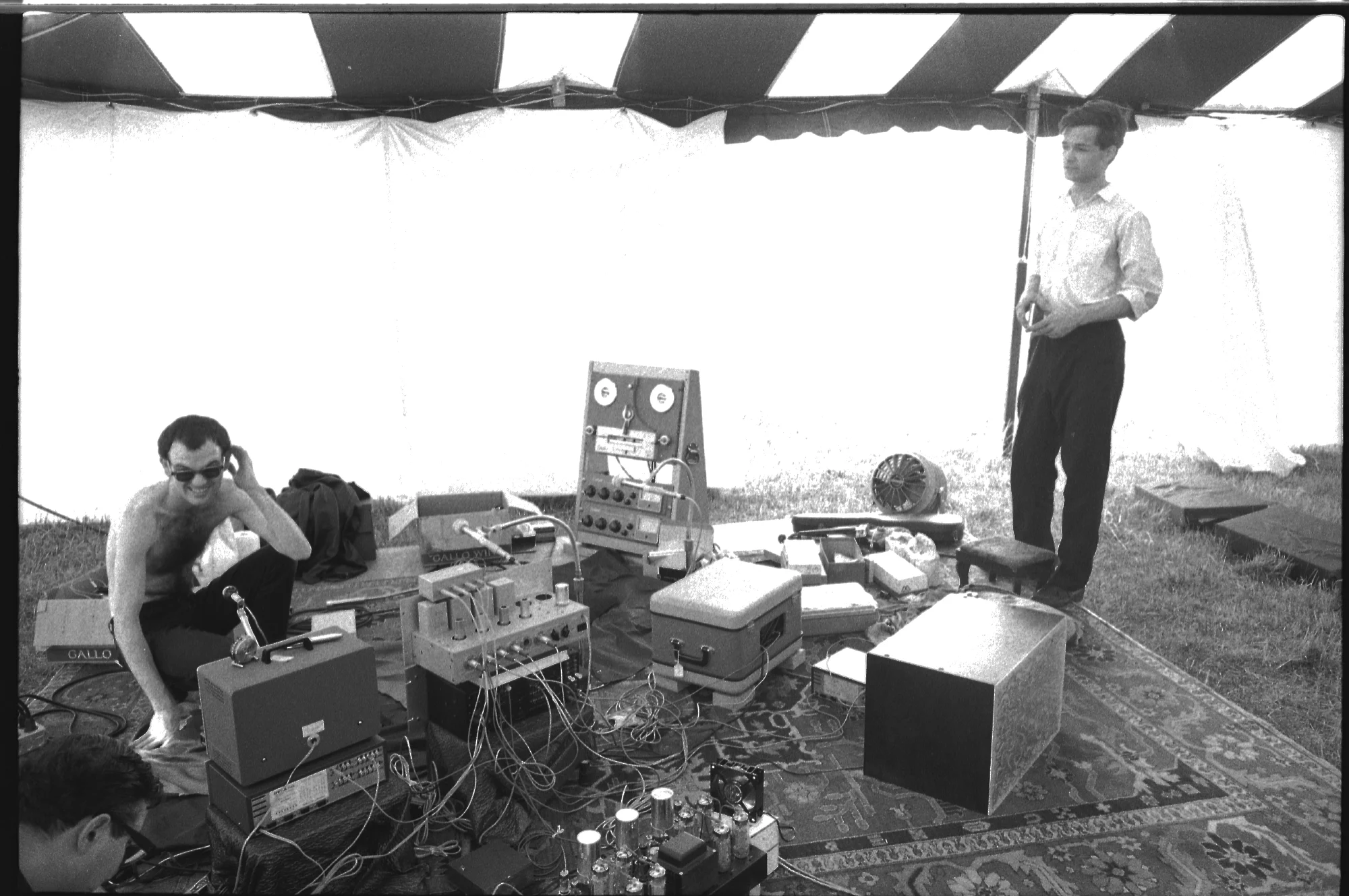

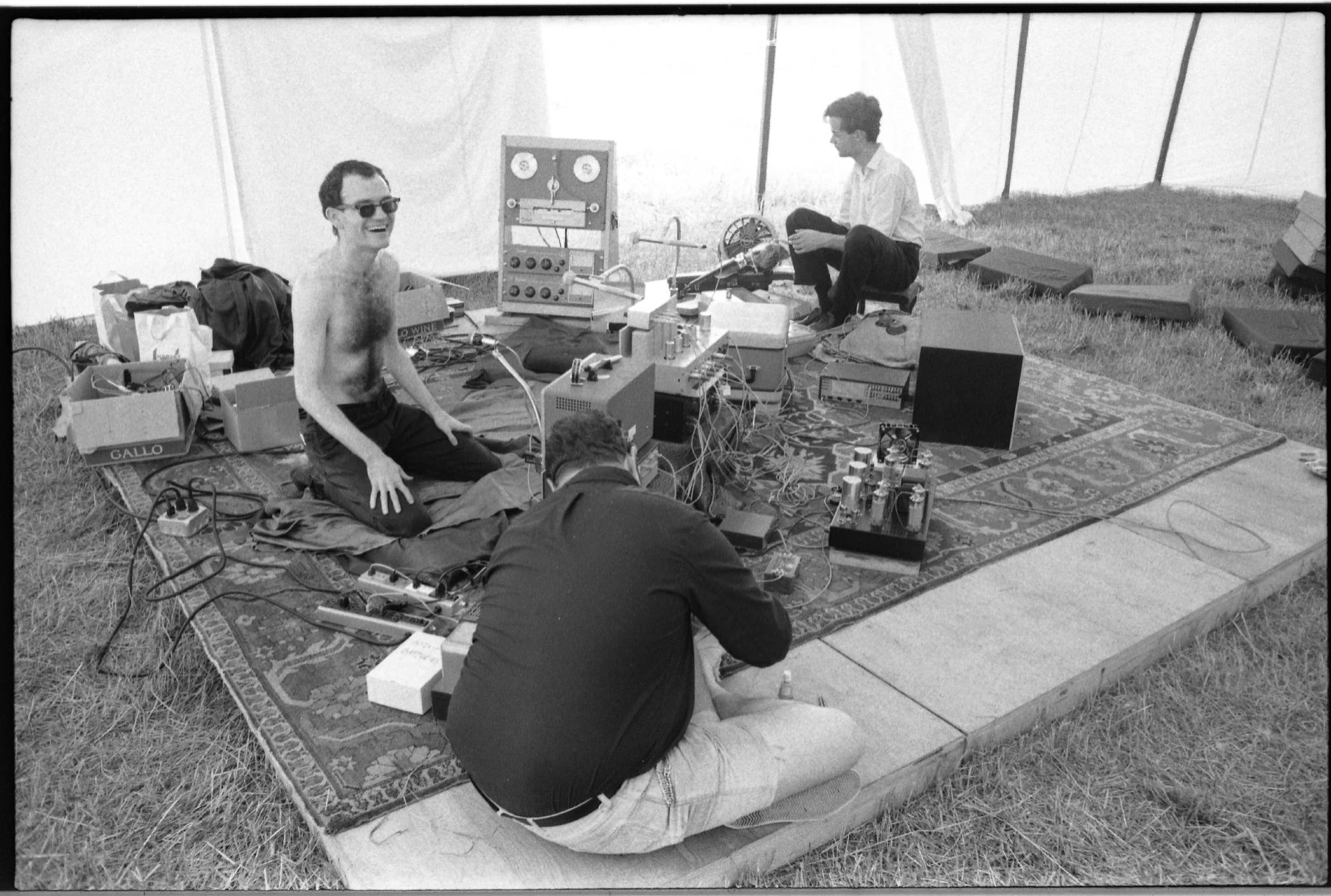

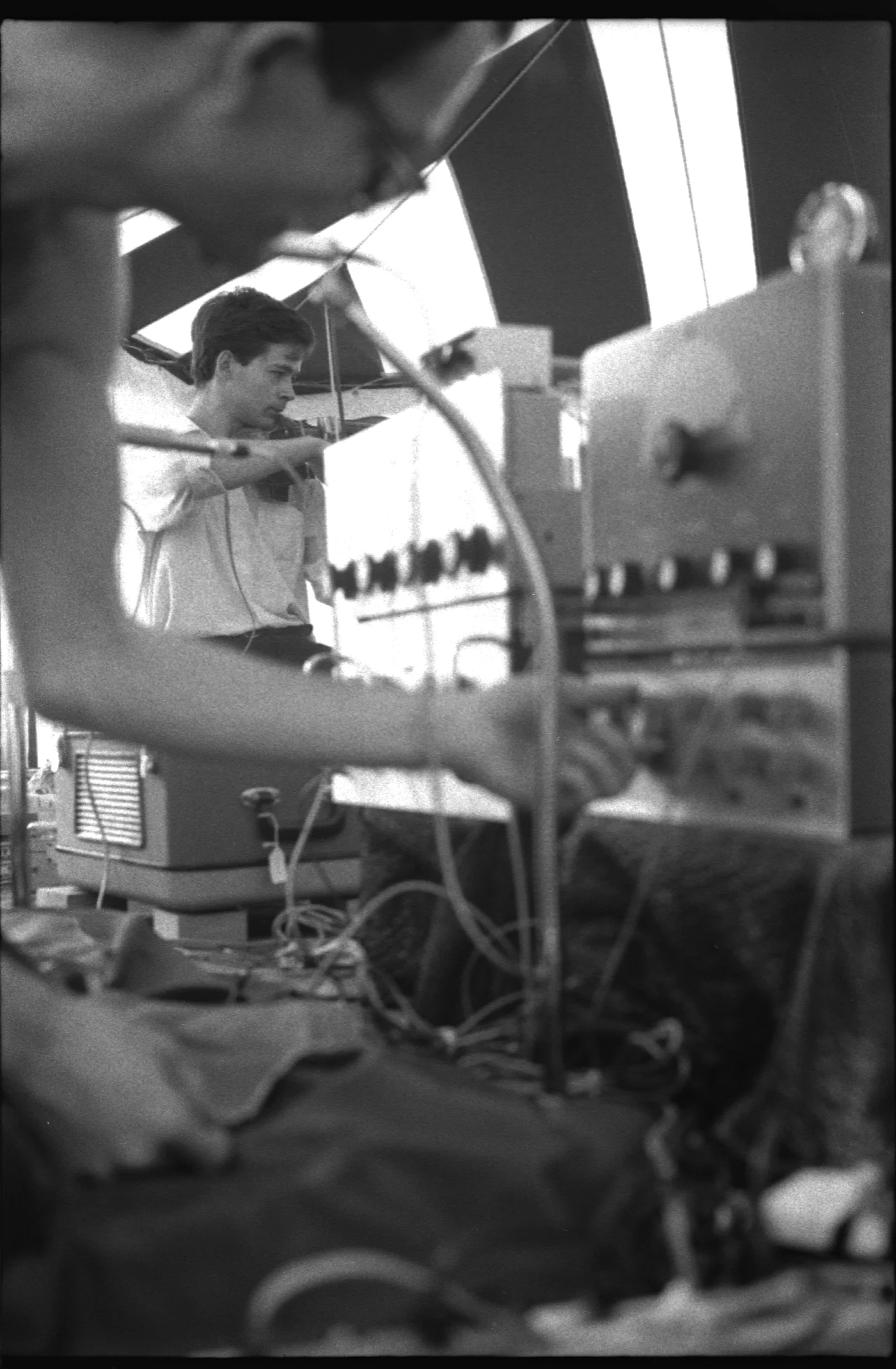

Here's what we know: in October 1972, at a hippie commune in WŸmme in southwestern Hamburg, a German art-rock collective bred on the stringent drone and skag-pop of the Velvet Underground hooked up with the young composer who gave that band its name-- or rather, who handed Lou Reed the sadomasochism exposŽ whence the band derived its name. Tony Conrad and the members of Faust collaborated for three days on an album that would be released the following year in England and would tank immediately thereafter. The musicians did not communicate or collaborate throughout the following two decades.

Minimalism is unquestionably the wrong word; I prefer asceticism. Anyone familiar with the Zappa-like hysteria of Faust's first album or the searing kosmische of IV must imagine the sheer force of self-denial at work in implementing Conrad's vision: to have a deep base note tuned to the tonic on Conrad's violin and to have the drummer "tuned" to a rhythm that corresponded to the vibrations. Minimal in design, I suppose, but catastrophically huge in execution.

"From the Side of Man and Womankind" opens in dead motorik, the usually nimble percussive battery of bass guitarist Jean-HervŽ Peron and drummer "Zappi" Diermaier, stalled out to a hollow thud-- like the heartbeat of a machine. Conrad's violin bleats mournfully, endlessly; rising, breathing, sighing, screaming, but without ceasing: relentless. Faust resisted. Peron's second bass note, inserted against Conrad's wishes, adds a spring and thrust to the proceedings. Zappi's odd cymbal crash shatters like punctuation in a prayer. Faust producer Uwe Nettelbeck dulled the serrated violence of Conrad's violin, somehow rendering slow murder into long caresses. "The Side of Man and Womankind" runs like a conveyor belt through fog: going without moving, advancing, standing still.

"From the Side of the Machine" is oddly less mechanical than its counterpart. A half-hour in length, like "Man and Womankind", the "Machine" side ruminates with muted psychedelia: serpentine bass, ceremonial percussion, the purr and roar of Rudolf Sosna's humming synthesizer, Conrad's violin passing high above like an electrical storm in the upper air. There is a predatory quality to the "Side of the Machine": an encircling peril, a certain restlessness above and behind. Mind moves, as if hunted.

The Thirtieth Anniversary Edition of Outside the Dream Syndicate adds a second disc of material. Two brief tracks-- both named with the young death of former Dream Syndicate comrade Angus Maclise in mind-- offer the remaining fragments of those three days at the abandoned schoolhouse studio at WŸmme. Both the slow burning "The Pyre of Angus was in Kathmandu" and the tremulous "The Death of the Composer Was in 1962" reveal a looser agenda in the sessions. In the latter piece, Conrad abandons the impassive drone of the first disc for an almost celebratory psych-rock. The second disc is rounded out by an alternate production of "From the Side of Man and Womankind", lacking the overdubbed violin lines of the album version.

So perhaps a little Zen, perhaps a little cataclysm. After all, as Lou Reed said, "It's the beginning of the New Age." And a few decades before that, a poet ended his long flirtation with Buddhism by joining the Church of England. In his conversion poem, however, he continued to pray with eastern paradoxes. "Teach us to care and not to care," T.S. Eliot intoned, "teach us to sit still." And this album finally begins to show us how.

Pitchfork Media

Tony Conrad with Faust

The Pyre of Angus was in Kathmandu/

The Death of the Composer was in 1962

1993

Table of the Elements

[Lithium] TOE-SS-3

7" single, four-panel enclosure, clear vinyl, hand-numbered

"'From the Side of the Machine' is oddly less mechanical than its counterpart. A half-hour in length, like 'Man and Womankind,' the 'Machine' side ruminates with muted psychedelia: serpentine bass, ceremonial percussion, the purr and roar of Rudolf Sosna's humming synthesizer, Conrad's violin passing high above like an electrical storm in the upper air. There is a predatory quality to the 'Side of the Machine': an encircling peril, a certain restlessness above and behind. Mind moves, as if hunted.

"Two brief tracks-- both named with the young death of former Dream Syndicate comrade Angus Maclise in mind-- offer the remaining fragments of those three days at the abandoned schoolhouse studio at Wumme. Both the slow burning 'The Pyre of Angus was in Kathmandu' and the tremulous 'The Death of the Composer Was in 1962' reveal a looser agenda in the sessions. In the latter piece, Conrad abandons the impassive drone of the first disc for an almost celebratory psych-rock."

Pitchfork Media

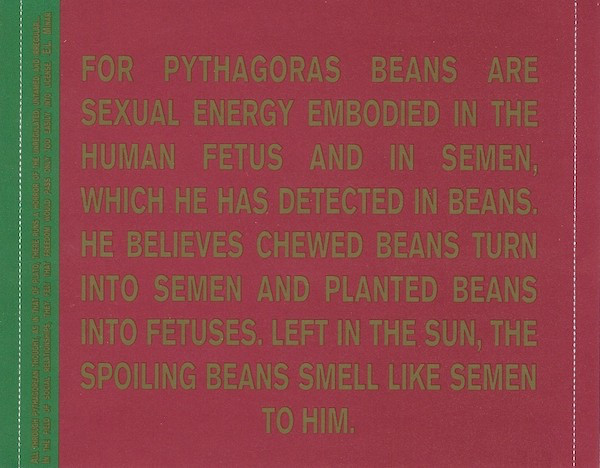

Tony Conrad

Slapping Pythagoras

1995

Table of the Elements

[Vanadium] TOE-CD-23

Compact disc, poster, obi

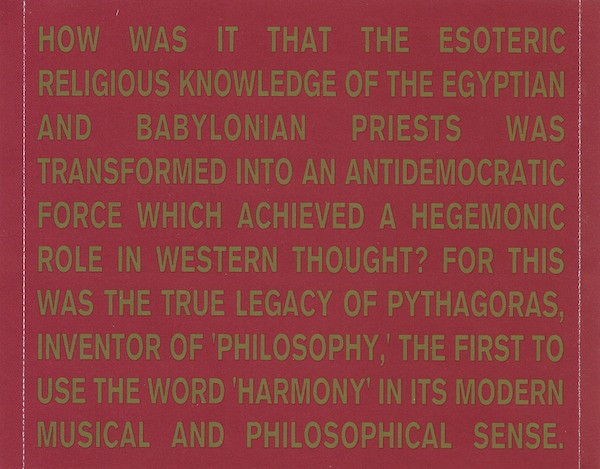

Tony Conrad is one of the most compelling figures in 20th century music, but it was this 1995 Table of the Elements release that defiantly established his relevance and influence for a new generation of listeners.

Conrad's previously obscure past is now well documented. In 1962 he co-founded the groundbreaking minimalist ensemble informally known as the Dream Syndicate. Wielding a drone both aggressively confrontational and subtly mesmerizing, he and his collaborators—including La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, John Cale and Angus MacLise—created some of the most revolutionary music of that—or any—decade. A chasm continues to widen between Conrad/Cale and Young/Zazeela and their starkly differentiated philosophies, as Young refuses any and all access to their extensive and collective archive of recordings.

Following the dissolution of the group in 1966, Conrad played a pivotal role in the formation of the Velvet Underground, before refocusing his efforts on experimental film and video. However, he did briefly and momentously reappeared to jam with German group Faust on the notorious 1972 LP, Outside The Dream Syndicate (also available as a double-CD on Table of the Elements). For another two decades, this remained his only available studio recording.

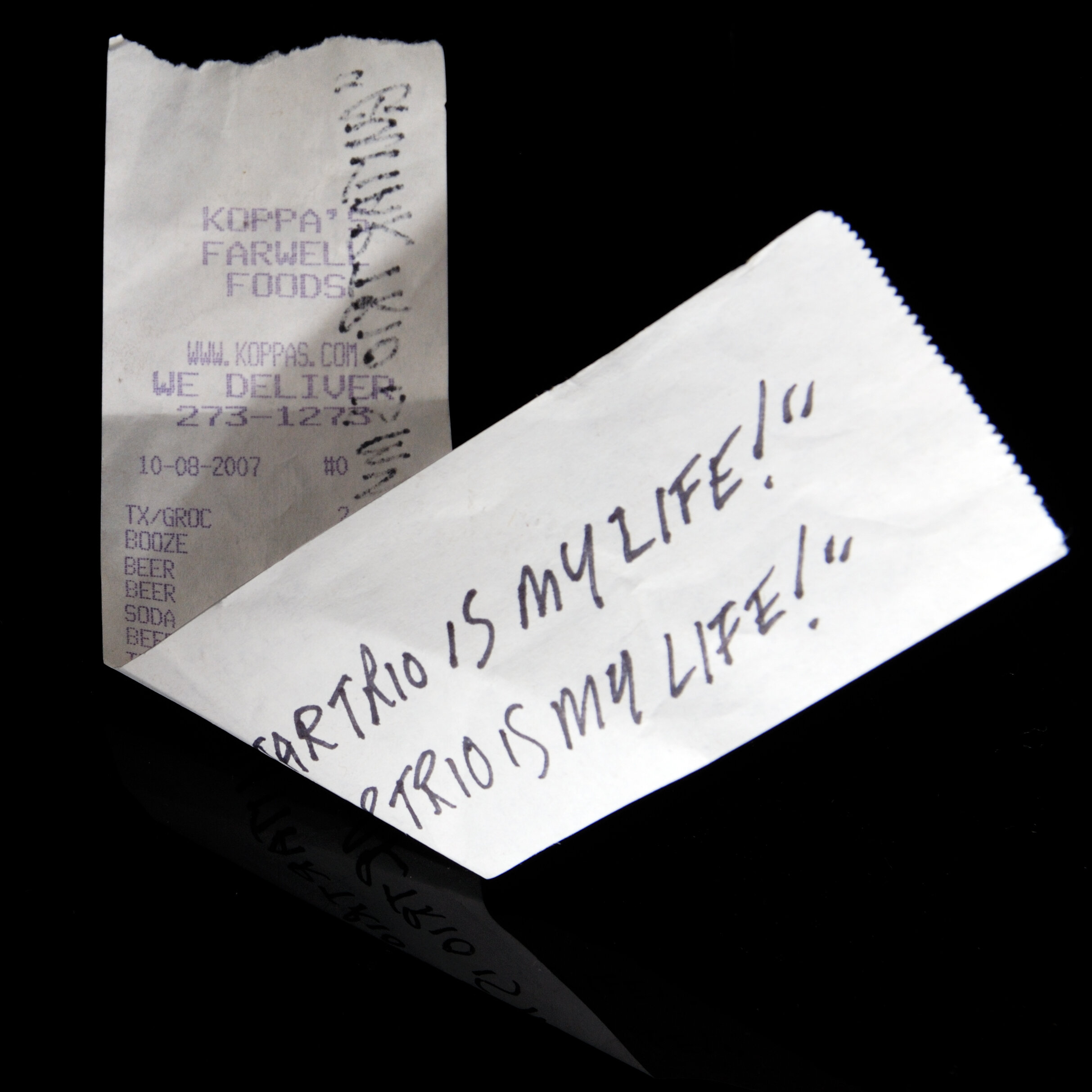

In 1994, Table of the Elements devised a daring approach to return Conrad to the recording studio and afford him an opportunity direct a new ensemble gathered from Chicago’s burgeoning post-rock scene. Over the years, Conrad had repeatedly groused that Faust’s producer Uwe Nettlebeck had mixed him soft on Outside the Dream Syndicate, which in Conrad’s words, made him “sound like a hippie.” With some prescient determination, the label arranged for Conrad to record at Electrical Audio, with engineer Steve Albini.

Albini had just rattled the music industry by refusing to dilute his raw, bellicose mix for Nirvana’s In Utero: His was a studious and methodical close-mic’ed attack that eschewed commerce for aural iconoclasm. While it freaked out the suits in Los Angeles, this sensorial vérité was delightfully attuned to Tony Conrad’s personal aesthetic. The sessions, piloted with crackerjack brilliance by producer Jim O’Rourke, finally captured with harrowing accuracy the Scrape und Drang of Conrad’s relentless and epic performance idiom.

The ultimate result was 1995’s micro- and macroscopic landmark, Slapping Pythagoras. It is as exhilarating, vigorous and downright antisocial as any great rock album—which is exactly what it is. Slapping Pythagoras reconfigures the lost dream music, addresses nearly thirty years of silence, and confirms Conrad as a giant in the soundscape of American music.

“In the beginning there was the Drone, the primordial, mind-splitting hum generated by the strings, keyboards and revolutionary lost-chord Zeitgeist of 60's group the Dream Syndicate ... Slapping Pythagoras is the sound of stasis in excelsis, the fluid microtonal Om of Conrad's violin resolving into deep pools of rich, alien harmony."

Rolling Stone

"Tony Conrad is a pioneer, as seminal in his way to American music as Johnny Cash or Captain Beefheart or Ornette Coleman, one of those really savvy old guys whom all the kids want to emulate because their ideas, their style are electric and new and somehow indivisible."

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Conrad invents a new musical language ... unbearably intense and gloriously ecstatic."

The Wire

“Slapping you Pythagoras, it makes me feel I’m rising, like watching falling water.”

Jim O’Rourke

Tony Conrad

Richard Youngs

Faust

Keith Rowe

untitled [“Nickel”]

1995

Table of the Elements

[Nickel] TOE-SS-28

7” single, hand-etched vinyl, cloth sleeve, silkscreen, poster

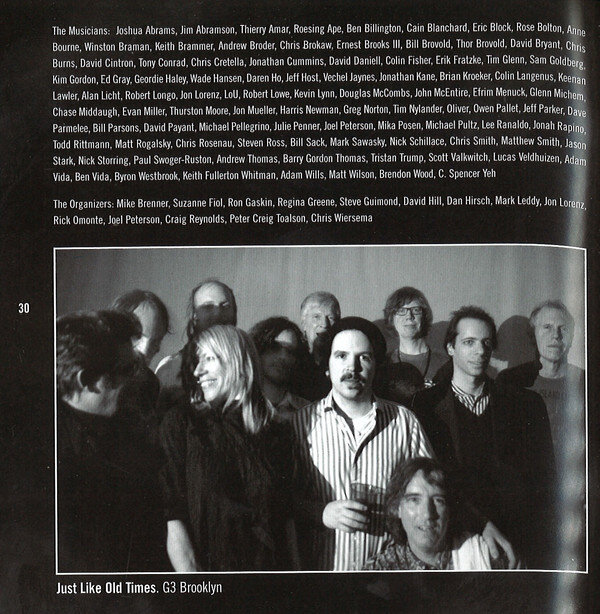

In the summer of 1995, Table of the Elements toured the U.K. and U.S. with these five artists, in various combinations. This single was pressed in an edition of 250 and given away for free at the shows. The A-side has five tracks, edited end-to-end by Jim O'Rourke (some recorded by O'Rourke and/or Steve Albini); the B-side is etched by hand and has details about the tour. The sleeve is cloth and silkscreened. The track from Faust was their first release of new studio material since the 1970s.

“This free record is for everyone who supported our live events in London, Manchester, NYC, Hartford and Chicago during February and June, 1995."

Tony Conrad

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain

with David Grubbs, Jim O'Rourke

Table of the Elements "Yttrium" Festival Chicago, IL

November 7, 1996

Director: Tyler Hubby

Projectors: Jeff Hunt, Dan Allen

Tony Conrad Collection no. 06)

Tony Conrad/Gastr del Sol

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain

Gastr del Sol

The Japanese Room at La Pagode

Tony Conrad

May

1995

Table of the Elements

[Copper] TOE-SS-29a

2x 7”singles, 21.75”x29” poster

Tony Conrad Collection no. 07)

Gastr del Sol

The Japanese Room at La Pagode

Tony Conrad

May

1995

Table of the Elements

[Copper] TOE-SS-29b

7”single, 21.75”x29” poster

“I went to the Japanese room at La Pagode to see an autobiographical film by a French director. It opened with footage of Cairo during the Gulf War. The director was represented by a milddle-aged Egyptian writer: same glasses. I was still weighing the merits of the Arabic voiceover when, unexpectedly, the film about Cairo ended and a film about the French Director began in earnest.”

“Why May Day? In honor of Maia, Roman ‘good goddess’ of fertility and women’s chastity, worshipped only by women. Love is not a suitable topic for music made by those whose history stinks of their habitual suppression of women. Why May Day? An international workers’ day in celebration of women and men together not as lovers but at labor. The high and low voices in polyphony signify women’s and men’s equity in a society unsoiled by the stain of love. Why ‘May Day!’ as men in distress face death? Love in music is only to yoke woman in opposition to man.“

“I had a dream that I shared a space with every living thing. Huge and waiting in the even light there stood a wall covered with windows and doors variously labeled with animal spoors and marked with names. As soon as I focused it clearly, each ancient door mysteriously became open, and a sound current flowed out all over the infinite plain. Other doors opened from time to time, reverberating the sound everywhere, but differently. And then suddenly there was nothing alive – but nothing had changed, and when I had returned, the sound was still there.”

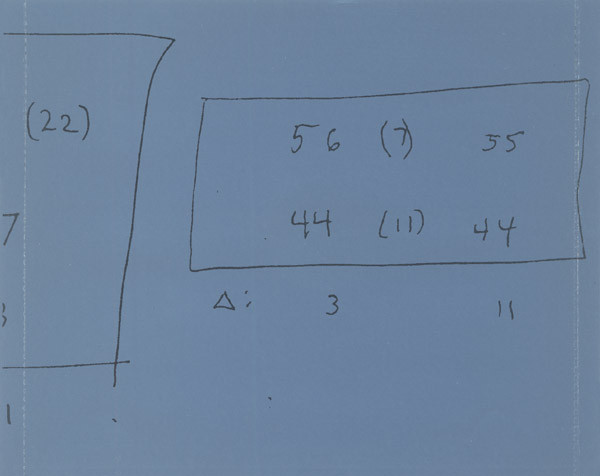

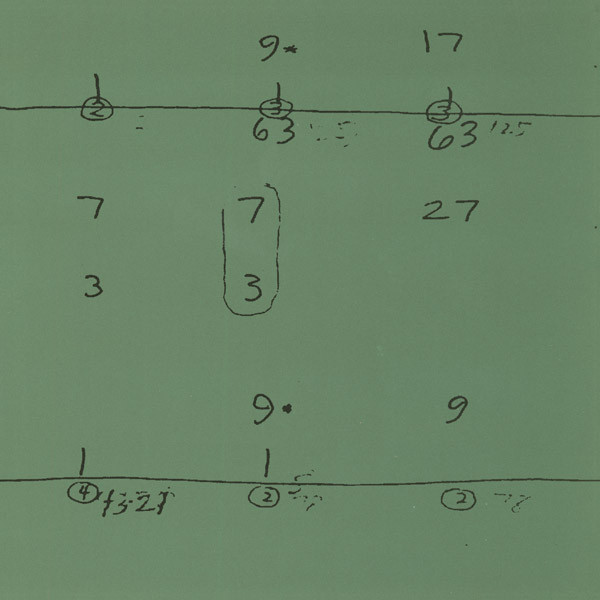

Available in limited quantities, this split Gastr del Sol/Tony Conrad record was originally released in 1995. The Gastr side features one of their earliest efforts at intensive multi-track recording; instrumental passages segue through the faint murmur of a thousand voices. Conrad’s contribution is excerpted from an unreleased version of Early Minimalism: May 1965, recorded at Steve Albini’s studio with Jim O'Rourke and Bob Weston (Shellac). The packaging is, arguably, the most lavish of any Table of the Elements release: the sleeve unfurls into a 21” x 29" poster, displaying texts by the artists in metallic plum and copper inks.

The first 500 copies contained a second record, featuring an excerpt from an unreleased recording of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (1971): Tony Conrad, violins; Jim O'Rourke, Long String Device; David Grubbs, bass. Recorded at Jim’s Steam Room studio, 1995.

“Completely mesmerising, the instinctively fearless results are belied by a conceptual and mathematical rigour that boldly asserted Conrad’s convictions in a unity and transcendence of all things. And yet whilst divorced from the visual aspect of the performance - a row of quadruple projections arranged side-by-side, incremental overlapping to form a pulsating picture - which was surely a major part of the piece, the sonic results still carry a potent meaning through its durational reinforcement of purely dissonant tunings and insistently dragging yet forward motion - an inexorable drive intently focussing themselves, and the listener, in the eternal traction of the present.

“In terms of that effect at least, we could compare the piece’s intensity and heightened hallucinogenic qualities with extended studies such as Éliane Radigue’s Transamorem - Transmortem, Alvin Lucier’s Music On A Long String Wire or Harley Gaber’s Wind Rises In The North, for example, yet there’s something utterly primal at play that bucks all those references, and appears closer to a prescient, overproof distillation of folk immediacy, rock’s lusting urge, and the hypnosis of tribal/trance/techno musics.

“It’s a completely stunning piece of music that will repay the attentive, attuned listener with endless rewards.”

Boomkat

“Gastr del Sol’s musical universe is filled with juxtapositions; for years Grubbs and O'Rourke have constantly futzed with the musical boundaries of the hybrid genre of “innovation,” one they seem to spontaneously reinvent. “

Artforum

"Tony Conrad is a pioneer, as seminal in his way to American music as Johnny Cash or Captain Beefheart or Ornette Coleman, one of those really savvy old guys whom all the kids want to emulate because their ideas, their style are electric and new and somehow indivisible."

“[John] Cale left the Dream Syndicate for the Velvet Underground; Conrad found a community in avant-garde film. But after Reed fired Cale from the VU and he was at loose ends, he and Conrad revived their string-drone collaborations. Some of these works can be found on the box set John Cale: New York in the 1960s, released in 2000 on Jeff Hunt’s Table of the Elements label. Hunt, who played a big part in Conrad’s return to music in the early 1990s, is one of the film’s most articulate expert witnesses to Conrad’s artistic achievements. … In 2000, Table of the Elements finally released digital remasters of three early-’60s Dream Syndicate recordings, which Hunt says appeared mysteriously in the mail one day, as well as the boxed set Tony Conrad: Early Minimalism, which includes one work that is actually “early,” Conrad’s divine Four Violins (1964), as well as other disks by Conrad, MacLise, and Jack Smith.”

Amy Taubin, Artforum

Tony Conrad Collection no. 08)

Tony Conrad

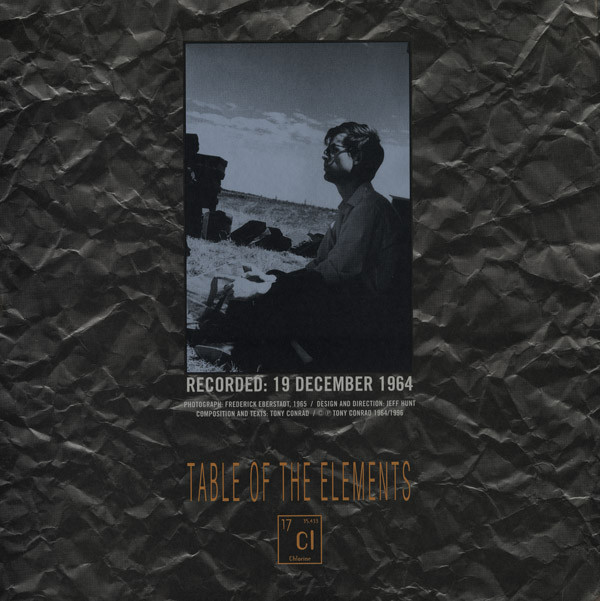

Four Violins (1964)

1996

Table of the Elements

[Chlorine] TOE-LP-17

Phono LP, 180 g. vinyl, gatefold jacket, poster

In 1962 Tony Conrad's amplifed strings introduced the sustained drone of just-intonation into "minimal" music. Conrad, together with John Cale, Angus MacLise, La Monte Young, and Marian Zazeela formed a performance collaboration from 1962-65 sometimes known as the Dream Syndicate. Utilizing long durations and precise pitch, their aggressively mesmerizing "Dream Music" denied the activity of composition, articulated their shared ideas of performance, and established the Big Bang of "minimalism."

When this remarkable group dissolved in 1966, their many rehearsal and performance recordings were repressed by Young and Zazeela, and became the stuff of legend. Conrad himself stepped outside of the Dream Syndicate once: on December 19, 1964 he recorded Four Violins, his only 1960s solo tape of violin playing.

Beautifully packaged in a gatefold jacket with metallic inks, pressed on superior-grade, 180 g. vinyl.

"The most striking quality of Four Violins is its instant familiarity: the grating sound of the violin parts imparts a vision of a uniquely American distance, the feel of a continent. It's a quality also present in the spaces surrounding John Fahey's or Loren Mazzacane's rattled notes, the early Sun recordings, the compositions of Charles Ives, the righteous soul-breath of Albert Ayler. With Four Violins Conrad moves closer to sound-essence, to ringing out the notes which have always existed in the skies of America.

"The joy comes from connecting with Conrad's language, from following its own logic—like railroads roaring out into the Midwest. This is a landmark recording in every sense, and the fact that this is only the first of many forthcoming Conrad installments from Table of the Elements makes me feel like howling with joy."

David Keenan, The Wire

"Tony Conrad is a pioneer, as seminal in his way to American music as Johnny Cash or Captain Beefheart or Ornette Coleman, one of those really savvy old guys whom all the kids want to emulate because their ideas, their style are electric and new and somehow indivisible."

Steve Dollar, Atlanta Journal-Constitution

"Minimalism's critical document... Astonishing"

Art Papers

"100 Records That Set the World on Fire"

The Wire

"Totally uncompromising ... a marvel."

Artforum

"The perfect sound."

Chicago Reader

"Brain-blistering."

Luna Kafe

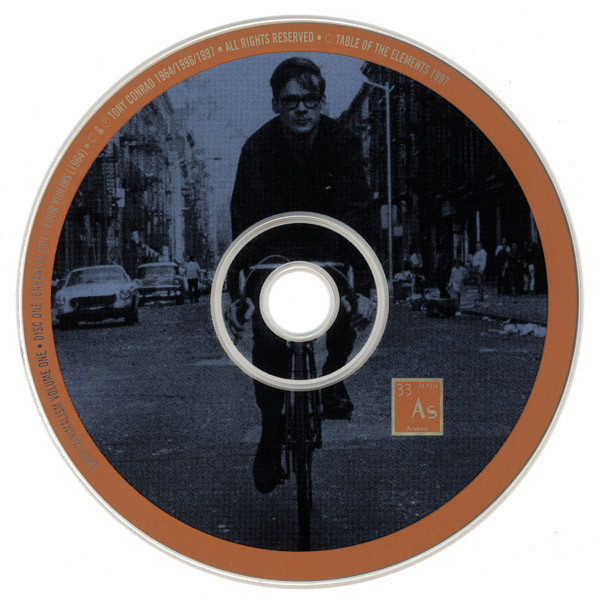

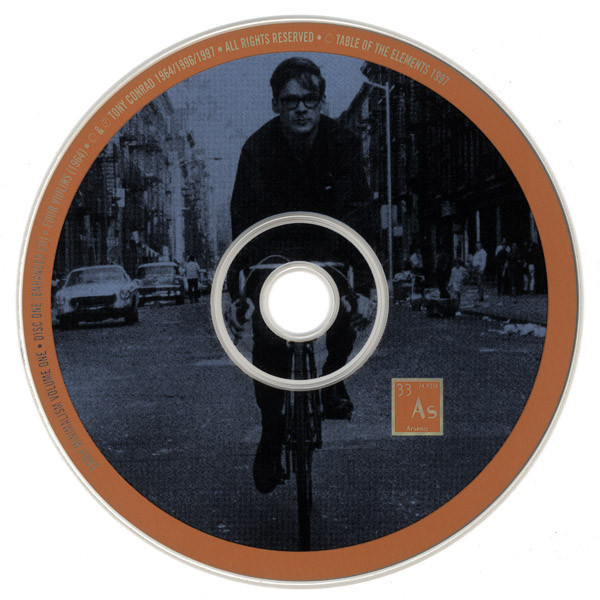

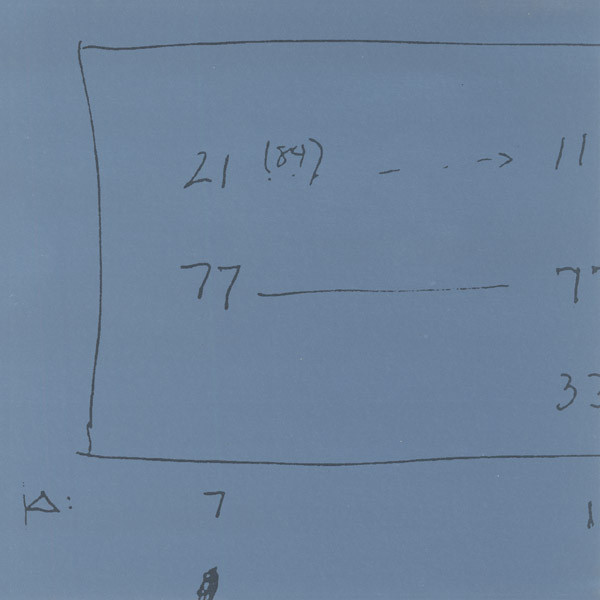

Tony Conrad Collection no. 09)

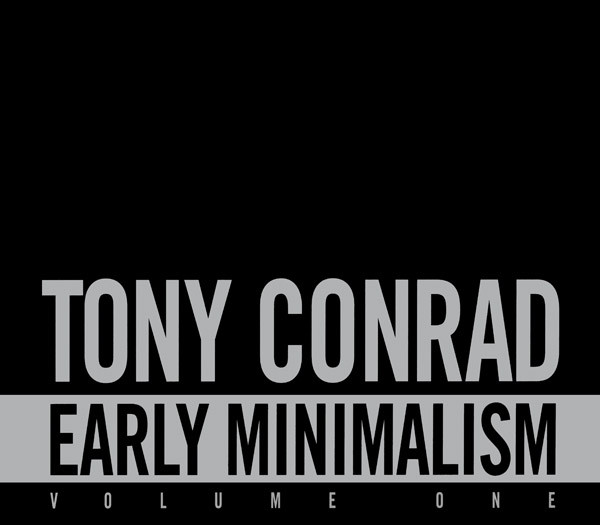

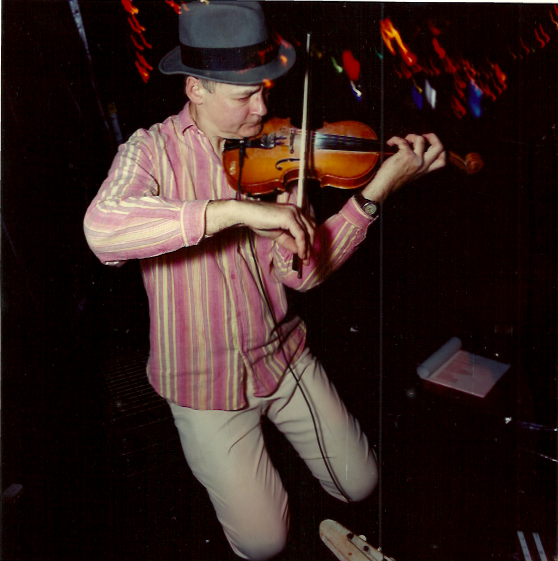

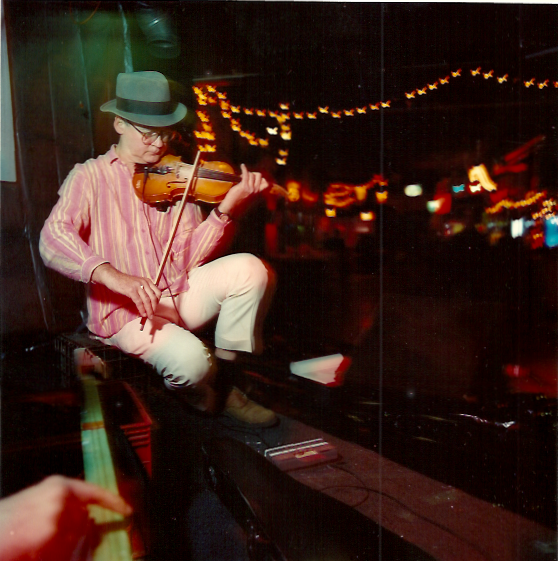

Tony Conrad

Early Minimalism Vol. I

1996/2002

Table of the Elements

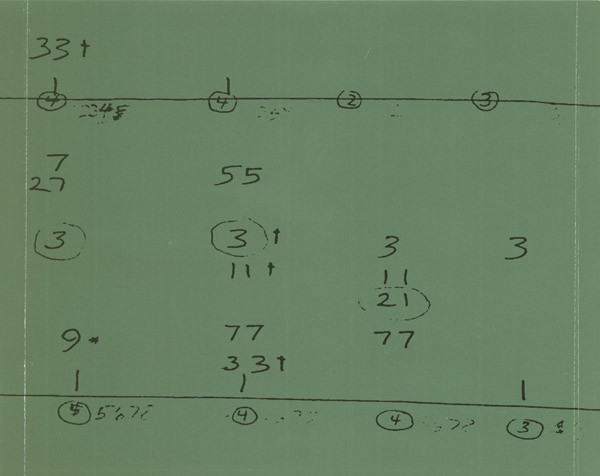

[Arsenic] TOE-CD-33

4x compact disc box, 112-page book, video, custom enclosure + catalog

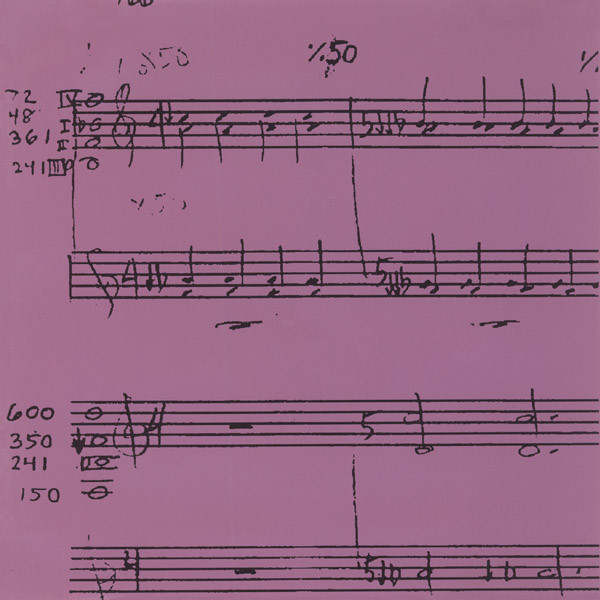

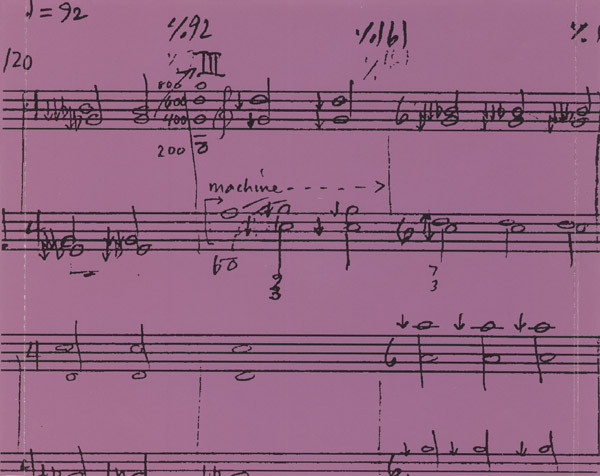

"History is like music—completely in the present.”

In 1962 Tony Conrad's amplified strings introduced the sustained drone of just-intonation into what came to be known as "minimal" music. Utilizing long durations and precise pitch, he and his collaborators forged an aggressively mesmerizing "Dream Music"—denying the activity of composition, elaborating shared ideas of performance, and articulating the Big Bang of "minimalism." However, the many rehearsal and performance recordings from this period were repressed, inaccessibly buried.

In 1987 Tony Conrad set out on a ten-year return expedition to the site of these entombed fragments to unearth the losses; from them he reconstituted and regenerated the epic Early Minimalism. Reaching back through time, Tony Conrad weaves a mobile narrative over and under minimalism: making music out of history, and history out of music.

“Tony Conrad is a pioneer, as seminal in his way to American music as Johnny Cash or Captain Beefheart or Ornette Coleman, one of those really savvy old guys whom all the kids want to emulate because their ideas, their style are electric and new and somehow indivisible."

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Early Minimalism, steeped in its history, is a victory for the highly influential Tony Conrad. What's more, the box set, along with its 90+ page-liner notes and CD-ROM, gives an excellent psychological look at a man who has refused to give in to injustice. Glorious."

Flagpole

“Tony Conrad invents a new musical language ... unbearably intense and gloriously ecstatic. A landmark recording in every sense."

The Wire

“Totally uncompromising ... a marvel."

Artforum

“The perfect sound."

Chicago Reader

“Groundbreaking."

Billboard

“Brilliant."

New York Times

"'Outrageous?' You should have heard the Dream Syndicate."

—Lou Reed, in response to critical attacks on his Metal Machine Music LP, 1975

John Cale

Tony Conrad

Angus MacLise

La Monte Young

Marian Zazeela

Day of Niagara (1964)

Inside the Dream Syndicate Vol. I

2000

Table of the Elements

[Tungsten] TOE-CD-74

Compact disc

"In the beginning there was the Drone, the primordial, mind-splitting Om generated by the strings and revolutionary lost-chord Zeitgeist of 1960's group the Dream Syndicate."

Rolling Stone

"'Outrageous?' You should have heard the Dream Syndicate."

Lou Reed, in response to critical attacks on his Metal Machine Music LP, 1975

From 1962 through 1965 John Cale, Tony Conrad, Angus MacLise, La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela participated in a collaborative ensemble that articulated the Big Bang of "minimalism." Utilizing long duration and precise pitch, they forged an aggressively mesmerizing "Dream Music"—denying the activity of composition and elaborating shared ideas of performance and improvisation. However, the many rehearsal and performance recordings from this period were repressed, and remained inaccessibly buried until this moment. Now, with the recent discovery of an additional cache of tapes, digitally restored and remastered, the world can step inside the Dream Syndicate for the very first time.

"This is a 31-minute drone. It's also probably the most important historical release of the year. After a decades-long wait, we're finally able to hear the original Dream Syndicate, the legendary ensemble of '62-'65, which influenced thousands solely through its reputation. It's the bite of Tony Conrad's razor-sharp violin, together with the blistering howl of John Cale's prepared viola, which makes this music so much more than so much of what's come after it. Conrad and Cale are the motor, producing a sound like the world itself exploding, only in slow motion and with absolute precision. An instant classic, still jaw-dropping after a 35-year hibernation."

Other Music

"Lou Reed's infamous Metal Machine Music; Jim O'Rourke's unlikely entrance in the pantheon of indie rock; and Sonic Youth's worship of the avant-garde; these instances and countless others were all born from the same seed: the legend of the Dream Syndicate. One of the most significant and controversial releases of 2000, Inside the Dream Syndicate is the high-throttle point when 20th Century Classical almost became rock 'n' roll. This is the Big Bang of Minimalism."

Pitchfork

"These recordings are (part of) a library of effort that represented, for Tony and I at least, a labour of love. The power and majesty that was in that music is still on these tapes."

John Cale

"The great missing link between classical and popular music—and Eastern and Western music—of the late 20th century. A monumental achievement."

Creative Loafing, Atlanta

"No lie, this might be the most historically significant music release of the last 20 years . . . A fantastic piece of deeply ecstatic sound."

Aural Innovations

"A heavenly din of hellish proportions. Definitely a coup for one of the most interesting labels in America, Table of the Elements."

Earpeace

“One of the most important recordings to emerge from the mid-1960's, a product of extraordinary sonic force.”

Boomkat

"A bracing and powerful document of a hugely influential ensemble that changed the sound of modern music."

Chicago Tribune

"Number 1 'Not-Pop' Release of 2000"

LA Weekly

"This music will drill you a third eye."

The Bob

"Downright loud and vicious."

Blastitude

"Exhilarating."

New York Times

"A bombshell."

Art Papers

"Amazing."

Village Voice

"Mindbending."

Spin

"The skyscraping wall of amplified string drone that is erected here towers over almost everything. Coupled with Cale's hypnotic, deafening, avant-rock viola is Conrad's equally impressive double-stop violin playing. Together they produce the sound illusion of some huge electrical generator, a grinding musical turbine that is forever shooting sparks to ignite the imagination... Day of Niagara is an incredible piece of music. That it exists and is, at last, available to anyone who wants to hear it is nothing short of a miracle. Rejoice!"

The Wire

“Ladies and gentlemen, forget about floating in space. We are floating in dreams-- dreams woven of sustained overtones, duration and pitch playing tricks on our ears and distorting our sense of time and place. It began with this, funny enough. Lou Reed's infamous Metal Machine Music; Jim O'Rourke's unlikely entrance in the pantheon of indie rock; all those SYR EPs and Sonic Youth's rectum-suffocated worship of the avant-garde; these instances and countless others were all born from the same seed: the legend of the Theatre of Eternal Music, La Monte Young's Dream Syndicate.

“One of the most significant and controversial releases of 2000, Inside the Dream Syndicate offers a glimpse behind the mysterious curtain. It's what you might have heard had you been fortunate and bold enough to sit in on one of the Dream Syndicate's legendary '60s performances. Mind-numbing waves of amplified strings, slowly bowed to maintain overlapping drones the likes of which you never thought you'd ever want to listen to-- alienating, enveloping sound, seemingly devoid of notation and sense.

"’Outrageous!’ was the cry when Lou Reed unleashed Metal Machine Music. ‘You should have heard the Dream Syndicate,’ was Reed's response. But don't let the band's name fool you: they're not to be confused with the Paisley Underground psych-pop band that adopted the moniker as a high-brow homage in the early '80s. This is the high-throttle point when 20th Century Classical almost became rock 'n' roll. This is the Big Bang of Minimalism. And just look at the star power: a pre-Velvets John Cale on viola; venerable avant-garde composer and filmmaker Tony Conrad on violin (he was Mercury Rev's mentor at SUNY Buffalo, don'tcha know); poet and percussionist Angus MacLise on tabla; and one of the weirdest, most visionary of artistic marriages in John Cage protégé La Monte Young and visual artist Marian Zazeela, who provide vocal drones and conceptual direction to the project.

“La Monte Young owns the original performance and rehearsal recordings of the Dream Syndicate and refuses their release, much to the frustration of Cale and Conrad. He insists that he should be credited to the sole "composer" of the music-- himself. Cale and Conrad have always maintained otherwise, that it was a collaborative effort in performance and improvisation, and that they shall never cede complete authorial credit to Young alone. This dispute, along with Young's intractable perfectionism, has prevented the world for the past 35 years from hearing just what those five headcases were up to.

“However, some high-quality bootlegs ("an additional cache of tapes," it's said) have surfaced, so here we have it: a healthy dose of controversy and confusion, and the first semi-legit release of Dream Music ever, credited to all five. La Monte Young is pissed, noting imperfections in the mix, length, etc. But any way you cut it, avant-garde indie Table of the Elements has balls, and this release is ideal.

“This music is not meant to be listened to on headphones. It is difficult, should fill space, bounce off walls, clear rooms, and mess with your head. Appropriate volume levels do not exist for what is on this disc. Originally, Dream Syndicate performances were debauched night-long endurance tests, presaging the vibrant rave scene that would follow. Goodbye 20th Century? I think not. The past always comes back to haunt you.”

Pitchfork Media

April 30, 2000

The Theater of Eternal Music performing in 1965. From left, Tony Conrad, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela and John Cale.

Tony Conrad Collection nos. 11) 12)

Tony Conrad

Fantastic Glissando (1969)

2003/2005

Table of the Elements

[Lead] TOE-LP/CD-82

Phono LP/compact disc, enclosure

It’s 1969, and Tony Conrad wants to take you Higher.

Celebrated for the thrilling roar of his amplified violin, Conrad is a founding father of ‘minimalism’ and a giant in the American soundscape. Now Conrad’s own Audio ArtKive imprint presents the first in a series of releases that reveal the wild breadth of his 40-year career, including field recordings, piano compositions, film soundtracks and more.

Fantastic Glissando (1969) is a series of [d]evolving electronic compositions created with sine-wave oscillators. The instrumentation is different, but the effect is typical Conrad: soaring, aggressively textured and jet-engine massive. This first-time CD release contains “Process Four of Fantastic Glissando,” a fifth track not included on the original LP version due to space limitations.

“Massive slab of temporal disruption from one of the most consistently wowing figures to come out of the cultural meltdown of the 1960s. Conrad was a key mover in the Lower East Side rock and avant underground in the early to mid 60s, playing with Lou Reed, John Cale and Walter DeMaria in Reed’s frat-rock combo, The Primitives, and standing in with early line-ups of The Velvet Underground. But it was his activities as part of The Dream Syndicate/Theatre Of Eternal Music, a group dedicated to extending waves of single note bliss into whole new zones of psychoactive ecstasy, that were to have the most far-reaching cultural impact. Alongside John Cale, Angus MacLise, La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Conrad founded a whole new approach to sound, working tiny pulsing intervals into long monotonal drones generated by bowed strings and vocals and birthing a minimalism several cells more blasted than the saccharine soundtracks associated with bigger hitting names like Philip Glass and Michael Nyman. Fantastic Glissando dates from 1969 and features four tracks of degraded sine-wave oscillations that approximate the roar of a fleet of V-2 bombers.”

Volcanic Tongue

“The media and reality: It's hard to attend both."

Tony Conrad Collection no. 13)

Tony Conrad

Bryant Park Moratorium Rally (1969)

2003/2005

Tony Conrad's Audio ArtKive/

Table of the Elements

[Bismuth] TOE-MP-83/TOE-CD-83

Free mp3/compact disc, matte varnish, matte enclosure, watermarked typing paper

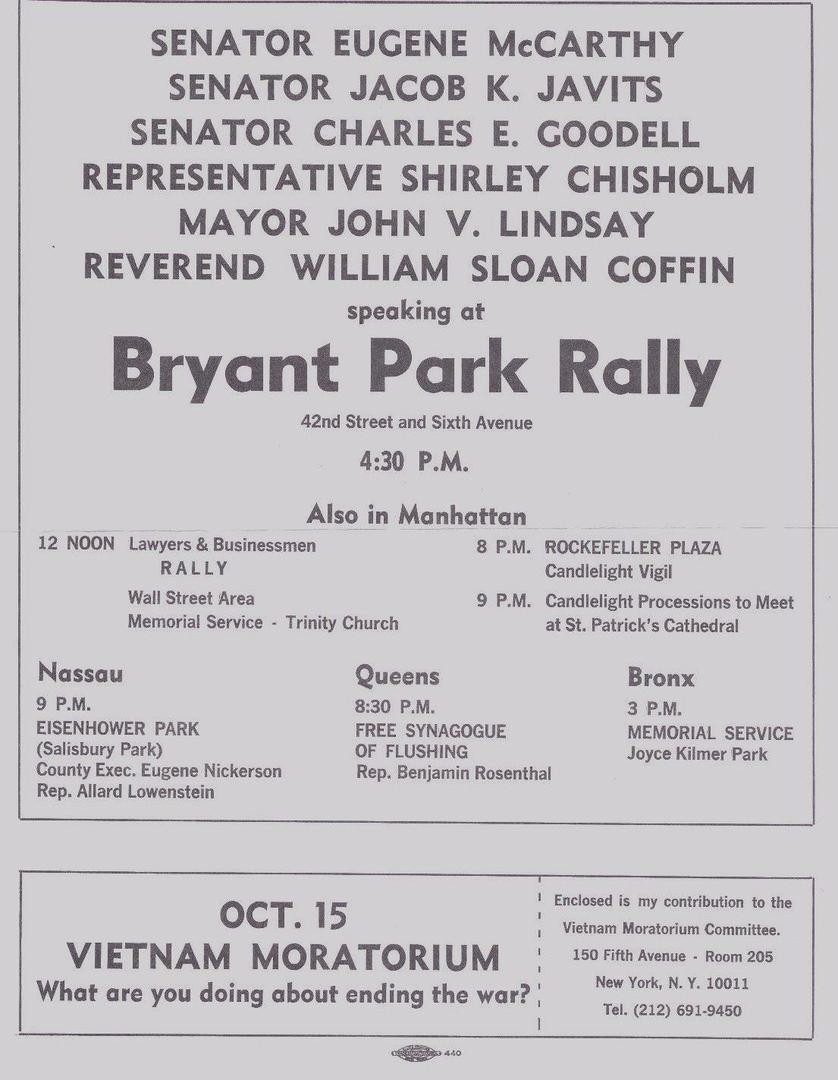

An October afternoon in 1969. Midtown Manhattan. A rally in Bryant Park against the Vietnam War. Down 42nd Street towards Times Square, Tony Conrad is adjusting microphones in his 5th floor loft, one directed at the TV set—where it will pick up live local news coverage—the other pointing out the window, where the echo of speeches and crowd noise mingles with the oceanic rush of crosstown traffic. As the event is about to begin, he rolls tape. Thirty-four years later, we hear what he heard. And the juncture, for so many reasons, could not be more critical. As the Bush Administration pursues a risky military agenda in the Middle East—one with unsettling long-term implications both at home and abroad—we see a nation not divided, as in the Vietnam Era, but strangely complacent. Our media-saturated reality functions like a drug, instantly televised warfare a new entertainment, and organized public dissent a novelty at home and a roaring chorus everywhere else. Conrad's recording of the Oct. 15 Vietnam Moratorium Rally is an eerie flashback that offers urgent new insights into our own lives and times, post-9/11 and full on into a new millennium.

"This was one event that I didn't have to leave the house to attend," says Conrad, whose recording coincidentally chronicles not only the rally—an archival moment—but doubles as a kind of sonic residue of a New York City that doesn't quite exist anymore, a place as swept away by the tilt of time and the circumstance of history as the twin towers. The Times Square area, now a Disneyfied circus of commerce suitable for morning show wallpaper, once was something far scarier and more radically chaotic. And it was from this perch that Conrad spent the afternoon. He remembers: "The street was awash with humanity, but no one lived there. It was like being in a desert in some ways. The number of voters were very small. There were people of every stripe and pandering to every kind of base and debased desire. There was a huge crossover, because millions of people came to work there every day, but it was also skin deep. People lived at the edge of the gutter."

The perfect place to make your life as an artist, amid the democratic bustle. That ruckus is key to this recording, which indulges the composer's interest in issues of documentation, the nature of public spectacles, and the deep biological impulses that govern the individual's response in the face of a mass. "What quickens your pulse in the wake of thousands and thousands of people?" he asks, while holding up this construct to a dual one. "That phenomenon of somehow the abstract voice of the media that comes down to us, can shape individual reality."

With that in mind, listen to how the two channels of this tape define the gap between media (the instantaneous leap of audio from a microphone in the park, transformed into a signal, and broadcast through his television's speaker) and reality (the delayed and muffled arrival of the same information at his window). It was funny, Conrad notes: "Because being there is later than TV. This brings up the phenomenological notion of the present, whether we live in it or after it. So you have this situation of TV vs. live, or TV vs. the street, all these issues of presence. The tape invokes that time really accurately and thoroughly. It's a big chunk, and that makes things so much more different than a sound byte."

The rally, part of that date's full slate of public demonstrations against the war, proves to be at once poignant and a bit comical. Powerful oratory from the Rev. William Sloan Coffin (who cites the gospel according to Pogo: "We have met the enemy, and he is us.") shares time with quips from Rod McEuen. A stageful of Broadway stars enjoy cameos ("Dick Benjamin!"), while Dick Cavett and Woody Allen chime in with quick comments. Leading anti-war politicos—such as Eugene McCarthy and Shirley Chisholm—take the microphone. It's a remarkable day in the life of a city.

"People really owe it to themselves to go to these things," Conrad says. "Because these occasions are such important markers of the events of our time. The moratorium rally put the media and the people side-by-side, and presents a very important idea that comes into the picture in today's protests as well. The media and reality: It's hard to attend both."

Steve Dollar

New York City

August, 2003

Tony Conrad Collection no.14)

Jonathan Kane’s February

Arnold DreyblaTt

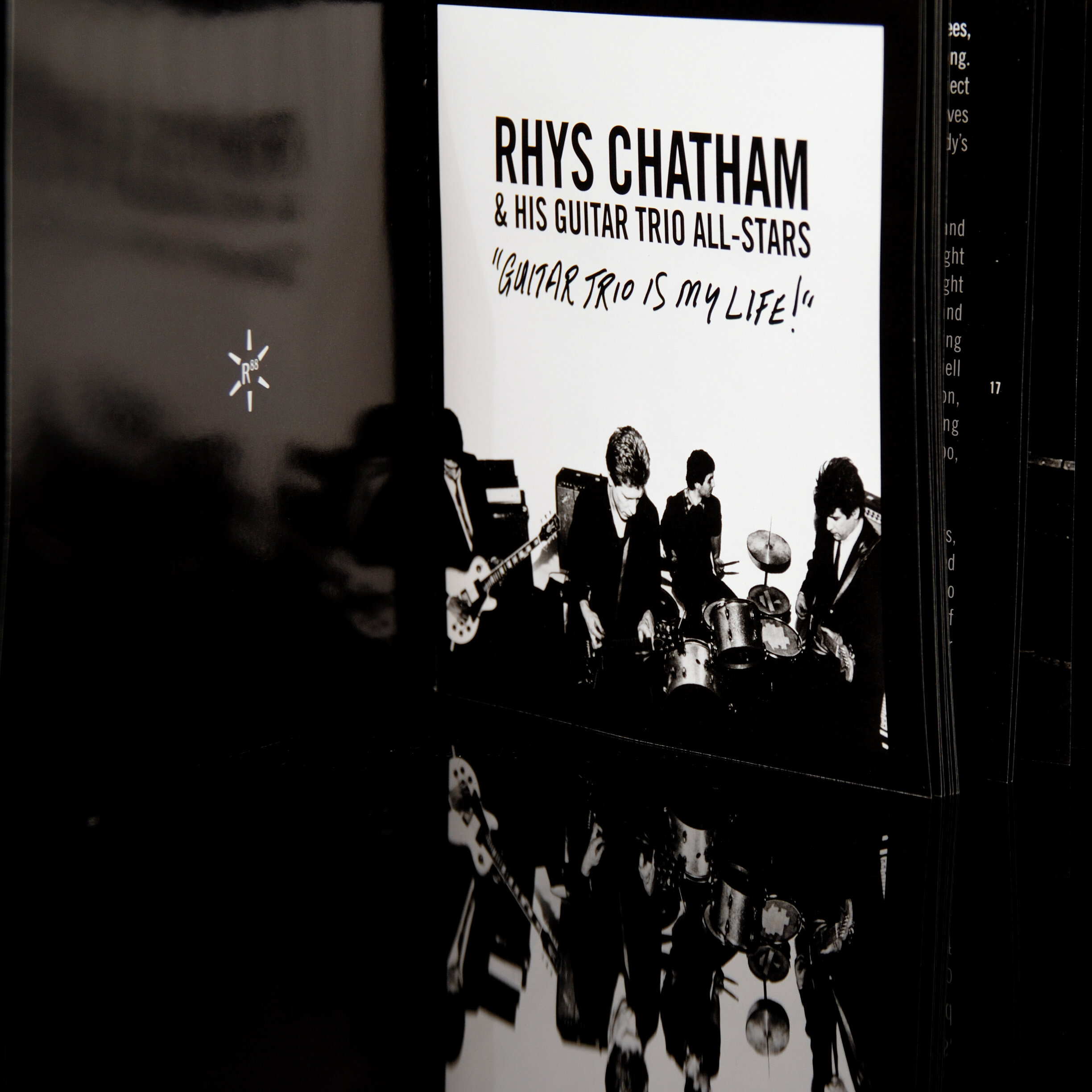

Rhys Chatham

Zeena Parkins

Tony Conrad

Tony Conrad with Faust

Leif Inge

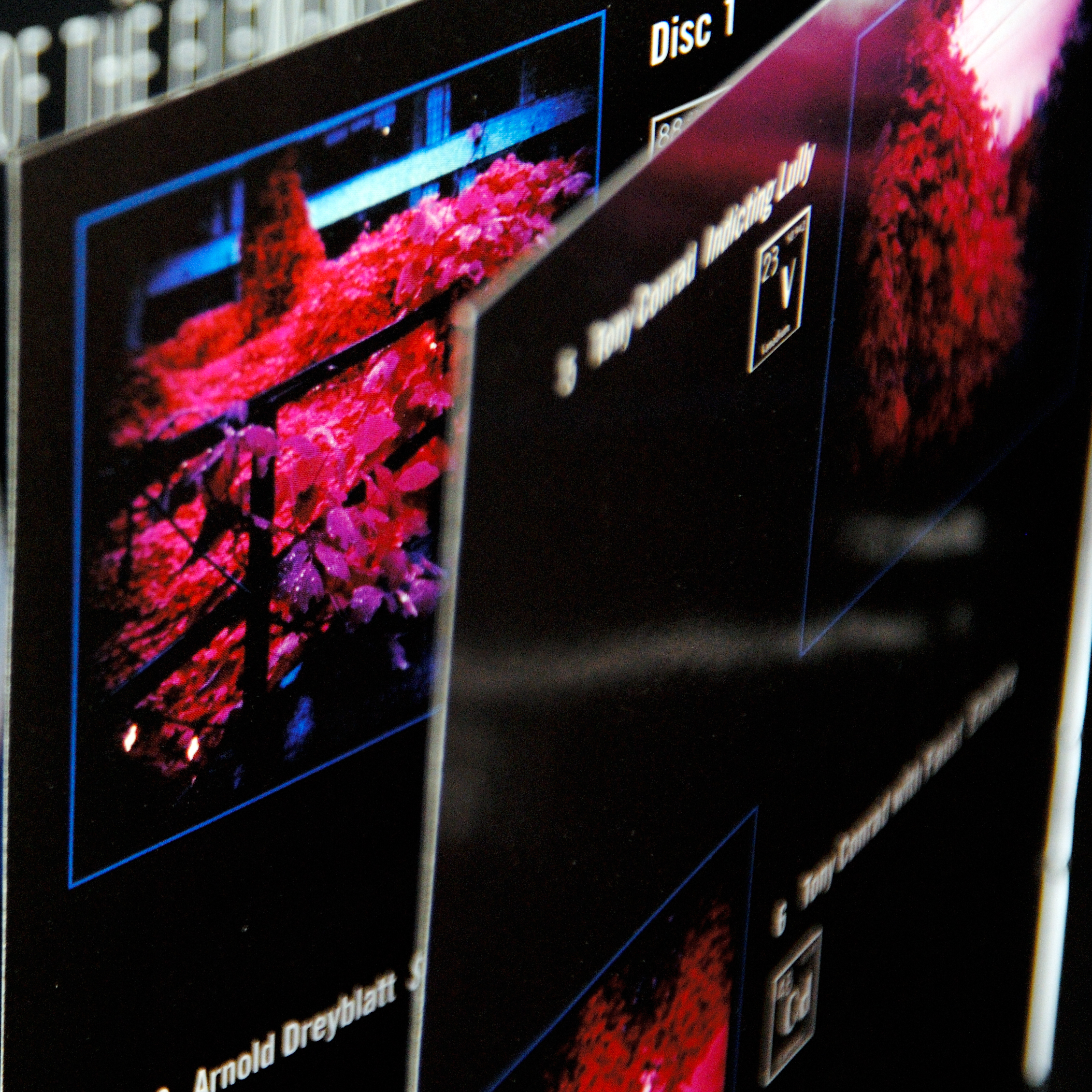

A Field Guide to Table of the Elements, Southeast Edition

2005

Table of the Elements

[Thorium] TOE-CD-90

2x compact discs, custom enclosure, booklet, 18 x 12” poster

Everybody loves a mystery. Generations of record collectors have spent valuable chunks of their lives poking through vinyl bins in search of unknown pleasures, or rambling through the piney woods with their ears cocked for a high, lonesome sound. Think of Harry Smith, magical curator of forgotten 78 rpm discs, whose “Anthology of American Folk Music” created a rich mythology out of grooves dusty with neglect. Even revolutionary sounds can come and go with the scarcest trace. That’s part of the power they hold over the ardent, would-be listener. The truth is out there.

Since 1993, Table of the Elements has spoken that truth. The label has staked its claim on a massive enterprise: It intends nothing less than to rewrite the history of American music in the second half of the 20th century. And beyond. That’s a tall order for even the largest multi-national corporations, whose vaults harbor so much of our cultural data. Imagine, then, the flinty ambition necessary for Table of the Elements to pursue its goal. This modestly funded, cellular organization has thrived on smarts, and pluck, in realizing its projects, which have focused on musicians whose light shimmers outside the frames of convention. The label’s 100-plus releases are a vital contemporary archive, a survey of meaningful eruptions across a broad horizon of improvised, experimental, minimal and outsider musics.

During the past 13 years, the pop world has seen grunge give way to crunk and CDs yield to MP3s. Technology has mediated an ever-more globalized marketplace in which music has been made at once ephemeral and privatized, freely traded yet increasingly consumed in isolation. Table of the Elements looked at the longer haul, registering the ripples of music that are too essential to die or dissolve into the common currency. The label went prospecting for the rarest sort of sonic lode, the uncut goods blessed with a hearty half-life. The New York Times praised these actions for single-handedly “rescuing the underworld of 1970s and ’80s music from cassette-recorded oblivion.”

The label’s signature artist, Tony Conrad — a violinist whose primal enveloping drones create an oscillating ritual theater — has been prodigiously documented in a series of releases. These range from sumptuous packagings of lost classics (Conrad’s 1973 collaboration with Faust, “Outside the Dream Syndicate”) to new projects alongside young artists that the composer has inspired (“Slapping Pythagoras”) to recoveries of lost concepts given new breath (the epic 4-CD box set “Early Minimalism”). Conrad is joined on the label by other profoundly influential composers whose radical styles defy textbook definitions and challenge accepted notions of the minimalist canon: Rhys Chatham, Arnold Dreyblatt, Pauline Oliveros, Eliane Radigue, Laurie Spiegel and Velvet Underground co-founder (and Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee) John Cale. Cale’s remarkable early recordings made prior to his rock career were compiled in the 3-CD set “New York in the 1960s.” Founder Jeff Hunt’s efforts achieved a critical mass in 2000, with the controversial release of legendary “lost” collaborations from 1964 between Cale, Conrad, and La Monte Young. “Day of Niagara: Inside the Dream Syndicate Vol. I” topped numerous year-end “Best Of” lists and was lauded as “the most historically significant music release of the last 20 years.”

The label, however, has not been limited to that singular agenda. As minimalism’s creation myth has been challenged and outlined anew, there were other demigods lurking in forgotten corners of the pantheon. These irascible, tough-nut characters make their own legends, but their iconoclastic nature often marks them as merely that. The 1990s was a good time to poke around the crumbling brick corners of American music. John Fahey, SRO hotel occupant and record-collecting aesthete, was in the cusp of a latter-day renaissance in the mid-1990s when he collided head-on with Table of the Elements. Fahey finger-picked his way back into the limelight as TotE presented the guitar wizard and one-man archive of primitive American musics in notable concert settings, performances that also were recorded — and now stand as invaluable moments, a series of last hurrahs, in a life that was too soon winding down.

* * * * *

Europe, too, offered adventure. When a band called Faust decided to reunite, the act prompted Table of the Elements to engage the group for an outrageous series of concerts. Synonymous with “Kraut Rock,” the May ’68 anarchists were a historical footnote when its members convened again after two decades and hopped over the Atlantic. The band lurched across America on a chaotic 10,000-mile road trip that careened from New York to Death Valley. On a more consonant chord, the now ubiquitous studio whiz and composer Jim O’Rourke received some of his earliest support as both an artist and producer from TotE; he was introduced to indie-rock legends Sonic Youth at the label’s 1994 Manganese festival (O’Rourke was for a time their fifth member and producer), and lent his invaluable gifts to many projects.

The label also has ventured beyond music proper into the art world. Jack Smith, the original “flaming creature” himself, is the subject of two home-recorded artifacts released on Conrad’s Audio Artkive imprint. The 1960s legend, a protean filmmaker and Lower East Side bohemian original, is only one of several artistic outsiders to find a comfy spot in the label’s catalog. Globally renowned provocateur Mike Kelley has been documented. Avant-rock voodoo daddy Captain Beefheart has been treated to a series of limited-edition releases, as have Sonic Youth guitar monsters Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo.

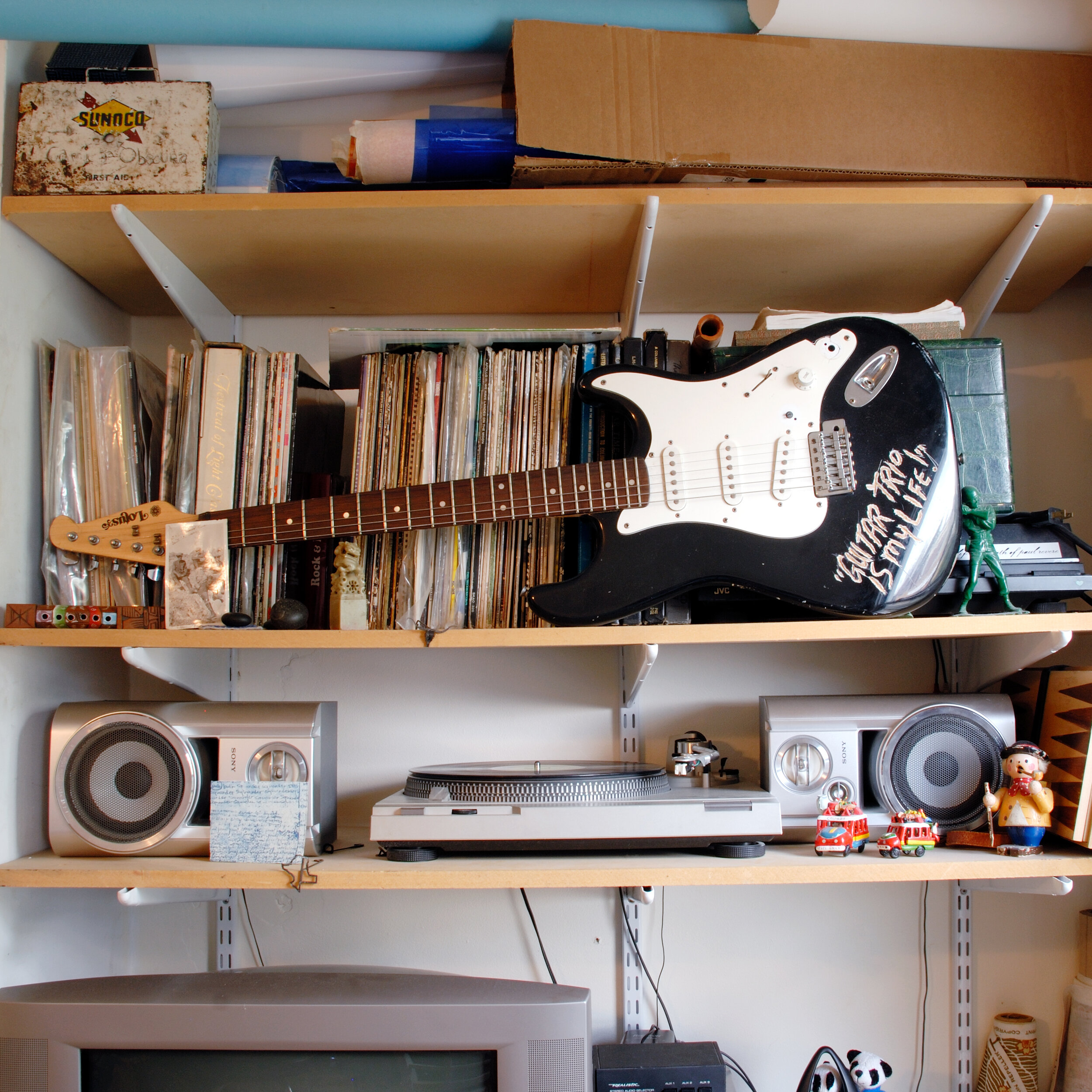

While other artsy independent labels have emerged in the wake of TotE’s initiative, none can match the verve with which its CDs, LPs and limited-edition sets are designed. Hailed by the leading bibles of American graphic and product design, Jeff Hunt, the label’s E E founder and art director, and his graphics cohort Susan Archie, of the World of anArchie design firm, are prime movers in a new wave of innovative music packaging. Their early, expressionistic use of metallic inks has been co-opted by the majors, while the label’s distinctive, elemental iconography has been assimilated into the mass culture through advertising for products ranging from Kool cigarettes to MTV. But there’s much more beyond such reverberations. Increasingly encyclopedic creations — for TotE, as well as for the Revenant and Dust-to-Digital labels — recall Renaissance-era cabinets of curiosities, or the sublime shadow-box constructions of artist Joseph Cornell — reliquaries of exotic minutiae, crafted with wood, metal, vellum, cloth, foil, embossed stamping and even pressed flowers. It’s the commodity as both miniature museum and theater, in which one can endlessly indulge in wonder, love and, yes, obsession. It’s not often that a record label casts an influence on a broader design aesthetic — think Blue Note in the 1960s, with its hip Reid Miles album covers — but as a string of Grammy nominations and awards for Archie attest, that’s exactly what’s happened with Table of the Elements.

Even the label’s location was offbeat. Most of its current work was accomplished from the deep Southern outpost of Atlanta, Georgia. Home to hip-hop’s biggest, blinging’est names, the city is a capital of American pop, yet as remote from most avant-garde tangents as it is central to the early history of blues and country music. With Spanish moss overhead and kudzu underfoot, it’s a place where the fleeting façade of contemporary life is constantly eroded by nature’s deliberate encroachments, where the ghosts of other times float in the limpid air, and expend their wrath in the afternoon thunderstorms that create thrilling percussive spectacles in the summer sky.

Table of the Elements is likewise spectacular: A conduit for history exploding in the present moment. As the next millennium unfolds, the label continues to spin forward, embracing the radical delights that fall before its springheeled path. Current projects include such imaginative leaps as sound artist Leif Inge’s “9 Beet Stretch,” excerpts from a massively slowed-down version of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. “What you hear in normal time as a happy Viennese melody lasting 5 or 10 seconds becomes minutes of slowly cascading overtones; a drumroll becomes a nightmarish avalanche,” wrote The New York Times. The label also has a live wire in drummer Jonathan Kane, whose CD “February” represents thrilling possibilities for its future. The music’s tintinnabulatory rush is hypnotic and bracing, an evocation of the blues that harks backwards and forwards at once. It’s the kind of music men might gather together to play on a moonlit night deep in some rural hill country, with trouble in the distance and whiskey close at hand. It’s the kind of music you might hear above a bodega, on an afternoon in the Lower East Side, with trouble everywhere and no end in sight. It’s the kind of music Table of the Elements is all about. It thrives outside the barricades, where no one else is looking. Where the truth is spoken.

Steve Dollar

New York City

August, 2005

Tony Conrad Collection no. 15)

Tony Conrad with Faust

Outside the Dream Syndicate ALIVE!

2005

Table of the Elements

[Cadmium] TOE-CD-48

Compact disc, print, foil stamp, stickers

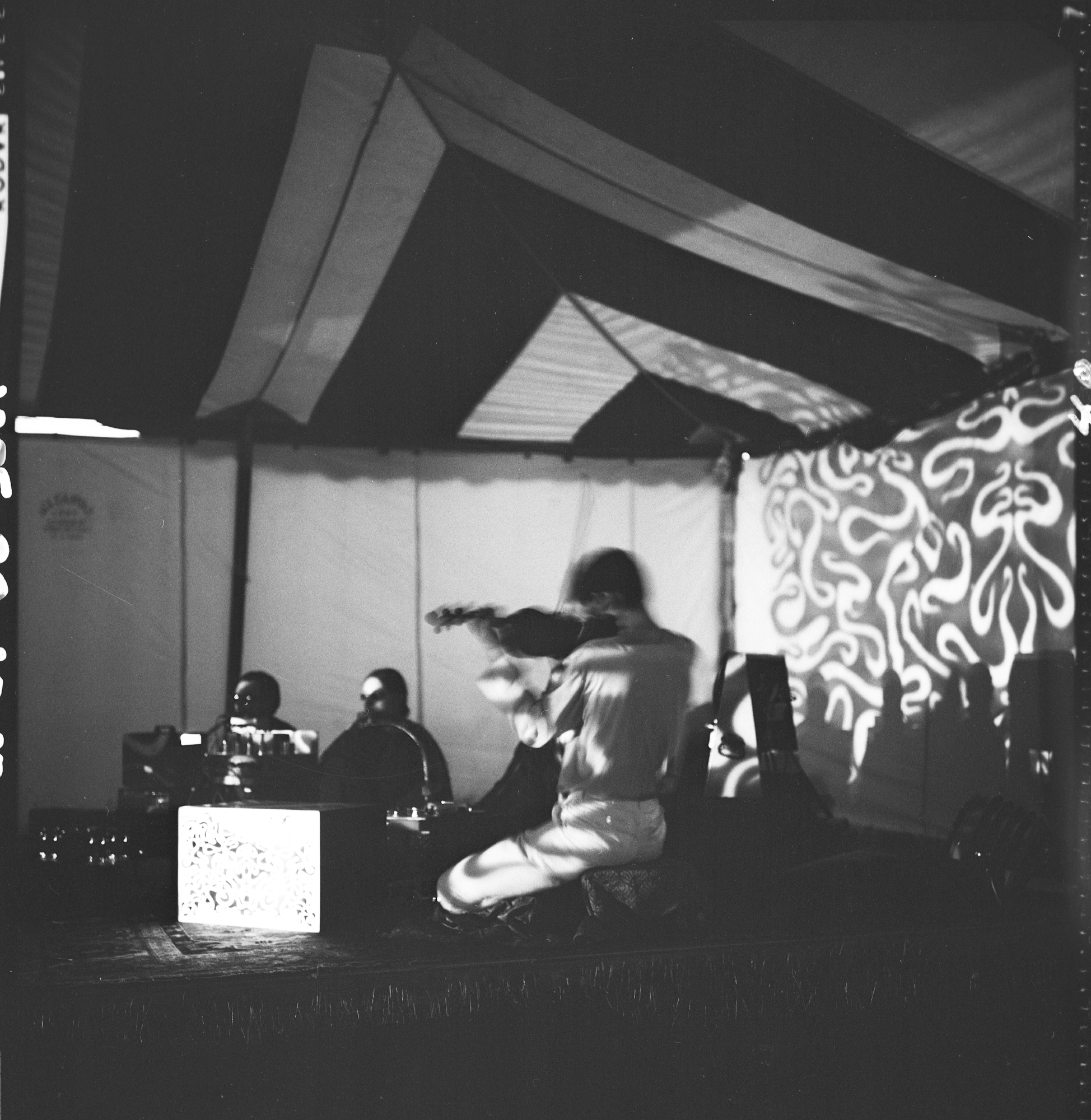

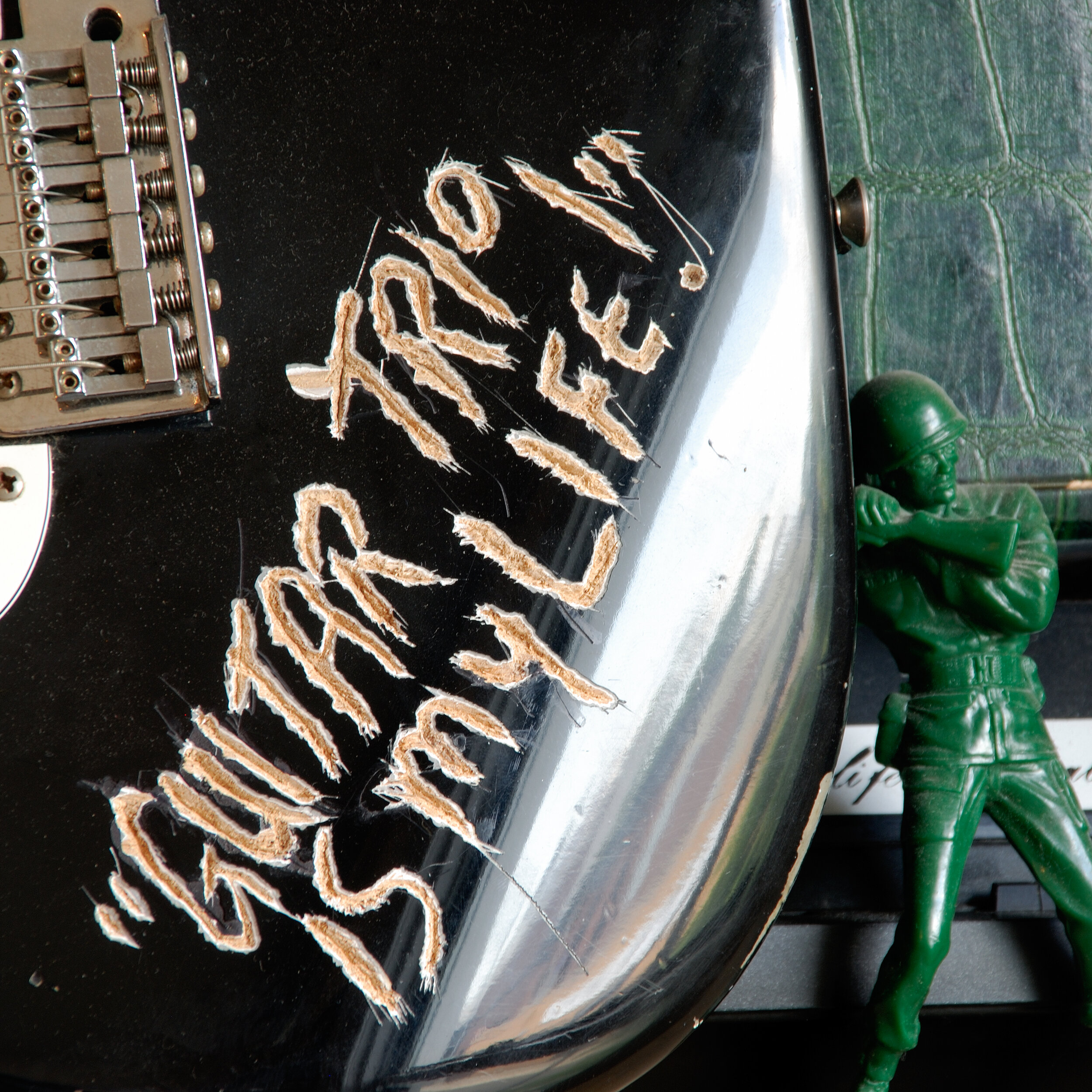

Minimalist pioneer Tony Conrad and notorious krautrock progenitors Faust met just three times: in the studio to record the groundbreaking "Outside the Dream Syndicate" in 1972, and twice on the concert stage in the mid-1990s. This recording documents their third and final encounter, at Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, February 18, 1995. The difference between the original session and this live event is astonishing. While Conrad's aggressive string sound was tamed in the studio by producer Uwe Nettlebeck (Conrad has complained that the mix made him "sound like a hippie"), here it is full of menace and ferocity, and in tandem attack with the equally belligerent violin of Jim O'Rourke, it conjures a raging wall of sound. When the Faust rhythm section finally kicks in, no one is in the mood for restraint, and the whole thing bolts on a merciless, scorched-earth gallop. Bassist Jean-Herve Peron plays with such fury that he snaps a string (no easy feat on a bass guitar), shreds the flesh on his fingers, and is soon covered in blood; meanwhile drummer Werner "Zappi" Diermaier pounds away, standing, in his inimitable, robotic style. After a relentless 40-minute onslaught, Peron signals the set's abrupt conclusion by smashing a brick with a sledgehammer, while Diermaier destroys his drum kit a la Keith Moon. At this point the elegant atmosphere of Queen Elizabeth Hall thoroughly disintegrates, and the antagonized crowd nearly riots. Hecklers and supporters continue to shout each other down -- until they're drowned out by a rollicking encore.

The booklet contains brief interviews with Conrad and Peron, and a first-person account from Gang of Four's Andy Gill, who sounds justifiably intimidated by the entire performance. The packaging includes alternate photos from the 1965 photo-booth strip that graced the original studio release, plus stickers and a silver foil stamp.

“A large curtain of scrim hides half the stage. In front of it, two men stand motionless, one a barefoot bassist, the other a balding drummer standing, Mo Tucker-style, behind a drum kit which, in the intervening 20 years, has shrunk to just one snare, one tom-tom and one cymbal. Behind the scrim, backlit so his shadow looms hugely, is Tony Conrad, the minimalist-violinist with whom Faust once recorded an album entitled Outside The Dream Syndicate. A cellist and another violinist sit alongside him, also motionless. Conrad plays a chord, then keeps on playing it, a piercing, mesmeric drone of immense, ear-endangering volume. Some time later — about 10 minutes into the performance — the other string players join in with similarly minimal intent, setting up a static harmonic drone which continues for another 10 or 15 minutes before the bassist and drummer suddenly launch into the kind of riff which Status Quo might have discarded as being too basic. The drummer bangs each drum alternately at regular tempo, looking for all the world as if he’s jogging on the spot; the barefoot bassist, meanwhile, pummels his instrument with such singleminded fury that, shortly after he begins, one of the thick, well-wound strings has snapped. Have you ever tried to snap a bass string? It’s not easy. Usually, you need pliers, but there are no tools available on-stage tonight. “

—Andy Gill, Mojo

“…Conrad masterfully created a piece that no matter when it was produced evokes such a strong physical reaction. This is raw, building, blistering, pounding, droning brilliance! The way momentum keeps building works its way into your body and about half way into the piece you can't stop from getting completely wrapped up in it. The droning violin, the dirty percussion, the gut wrenching passion underneath and above it all!

It's amazing how in these sounds you can hear so much of a handful of contemporary favorites: Godspeed You Black Emperor's explosive drama, The Dirty Three at their most wild and rocking, Swans/Angels Of Light's blistering poignancy, but it all ends up seeming sorta like little league in comparison to the blood and guts that oozes out of this performance. As always Table Of The Elements appropriately package the cd with the care it deserves including some nice short conversations with Conrad and two great stickers of Conrad's face. Absolutely recommended!”

Aquarius Records

“Apparently minimalist pioneer Tony Conrad and notorious krautrock progenitor Faust only ever met three times; once in the studio whilst recording 'Outside The Dream Syndicate' and twice onstage during the 1990's where they brought that album to life in the live arena. A recording of their third and final encounter, 'Outside the Dream Syndicate Alive' was taped at Queen Elizabeth Hall London on February 18th 1995 and acts as an astonishing diktat on the raw power afforded by the live arena. Worth owning for the blazing row that ensues between members of the audience after the show finishes alone (choice putdown: "shut the fuck up you middle-class prick"), 'Outside the Dream Syndicate..." is pretty hard going; with Conrad's aggravated strings gnawing at Jim O'Rourke's equally gobby violin, whilst Faust's rhythm section is typically merciless. Closing with a brick being smashed by a sledgehammer, this is not for the delicate hearted; but for those who relish a live experience that extends beyond over-priced T-shirts and spilt Stella, then 'Outside the Dream Syndicate...' is a thrilling experience.”

Boomkat

“It's amazing how in these sounds you can hear so much of a handful of contemporary favorites: Godspeed You Black Emperor's explosive drama, The Dirty Three at their most wild and rocking, Swans/Angels Of Light's blistering poignancy, but it all ends up seeming sorta like little league in comparison to the blood and guts that oozes out of this performance. As always Table Of The Elements appropriately package the cd with the care it deserves including some nice short conversations with Conrad and two great stickers of Conrad's face. Absolutely recommended!”

Amazon

“Have you ever tried to snap a bass string? It’s not easy.”

Interview with Tony Conrad and Jean-Herve Peron (Faust)

TONY CONRAD: I basically said, “Keep an even beat going throughout the whole thing,” which is almost impossible. When I worked with Faust, I told the bass player this, but they didn’t believe me. They don’t even remember working with me. When it all came back recently, they had no recollection at all of working with me. I think they knew the record existed, somehow Uwe Nettelbeck had sucked it out of them. There were probably many reasons for that, including the fact that somebody must have been burning a pot field around where they were working, because there was so, so much pot smoke in the air. It was incredible. And who could remember anything under those conditions. I told them that they should just keep the beat steady, but when you play like that for a half-hour, it’s really unbelievably difficult and painful. Like when we played at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, Jean was playing with great fervour. I said, “Let’s play for 50 minutes.” The set broke down and we stopped early, and he came back and he was very excited, and he showed how his fingers were bleeding. He was ready to play more — the flesh was actually stripped off his fingers, (laughs) it was a nightmare, I couldn’t believe it was happening.

Q: Why and how did the collaboration with Faust come about? Why did you choose them? Were you aware of their music?

TC: I was approached by a filmmaker in New York, who was aware of my music, who was from Hamburg, and he told me that he knew a producer who would be interested in me, and that maybe we could make a record. So we set up a date, and as a matter of fact, at the time I had been working as an electronics technician for a small company that was planning to send me to Paris. That was because I was good at sales, and we were going to have an expo in Paris. But then the kid who owned the company got his college roommate to learn the electronics instead of me boning up on my French, and his roommate went and I stayed at home. So I quit, and decided to go to Europe anyway. La Monte had been commissioned to do a room for [large annual German art show] Documenta in ‘72 and he hired me to be his engineer. So I did that, and when I was finished, I showed my films around, and went to Berlin, because I had, something more than a decade earlier, spent half a year bumming around in East Berlin, and I had all of these friends from this very strange scene, which is now part of some history that is so weird and gone that no one will ever understand how strange it was. But it was the most extraordinary situation I was ever in in my life, and I wanted to go back and hang out with my friends in East Berlin. And after I did that, I flew to Hamburg, and was met by Uwe Nettelbeck, who took me to this farmhouse, and there were these people hanging around out there, I didn’t know who they were. [laughs] It was these people Faust. And they had been, to some substantial degree, incarcerated in this farmhouse for months, and they had their partners and sexual liaisons and different social complexities enacted on a long-term basis within this farmhouse. It was a microcosm, where everything seemed to have been evolving in some strange way over the course of months and months. It was no wonder that they really didn’t really have a lot of involvement with me, and I thought of them as musicians that I could use in my record. But Uwe said that they wanted to do stuff too, so we did one that was my style, and one that was more like a rock ‘n’ roll style. That’s how there are two sides.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: Ohh Tony! The Queen Elizabeth Hall gig was quite something! I thought it lasted longer than 50 minutes though. Time is relative said Einstein and can be bent. Zappi and I (and Tony) agreed that I would stop the piece (someone had to stop it you know or else we’d just all dehydrate on stage as no one would dare stop it it first) and the sign was me hitting a cobblestone with a sledge hammer (just to make sure no one could incidentally overhear it), and that was my main concern during the whole show even when I lost my plectrum in the first five minutes and realized I did not think of a spare one; even when I broke the E-string on my bass; even when I saw blood dripping at my feet. The idea of this small, square, hard, granite stone and this small, hard, steel head and me, me being as the vector of a perfect trajectory ending with a clean impact and hundreds of people watching this... Oooh Tony, what if I miss? What if I miss?! This obsessive idea helped me through the whole show. The violins and the cello were burning their high-pitch ferociously equalized tones in my brain, Zappi was sweating his wild dog-sweat and the stone just laid there, waiting patiently for its fortune. That’s why I was so excited, at the end... Because it stopped... Because I did not miss.

Q: I was at the QEH gig and it really was an extraordinary experience. I’m sure it was more than 50 minutes as well.

J-HP: A strange thing began to happen after about 15 minutes where the way your ears work seemed to change; it’s hard to explain exactly but several people I spoke to felt the same. A few years later I spoke to Zappi about the gig and all he said was “I think it was very loud” — as indeed it was! I remember Jim O’Rourke and Tony fiddling at the mixing desk with a look in their eyes, which was a mixture of anger (the sound man did not meet their wishes obviously), amusement, mischief and insanity. The fact that people had the feeling that “something changed” is probably purely morphological: The great Lord designed our ear system with a “limiter” so whatever comes to our ears and exceeds whatever the Maker thought intolerable will be cut off. Our ears close! Yeah, Hallelujah, that’s high-tech, that is love, that is a wonder, and it is good.

“The man is just downright cool—about as cool as Hendrix, and almost always louder.”

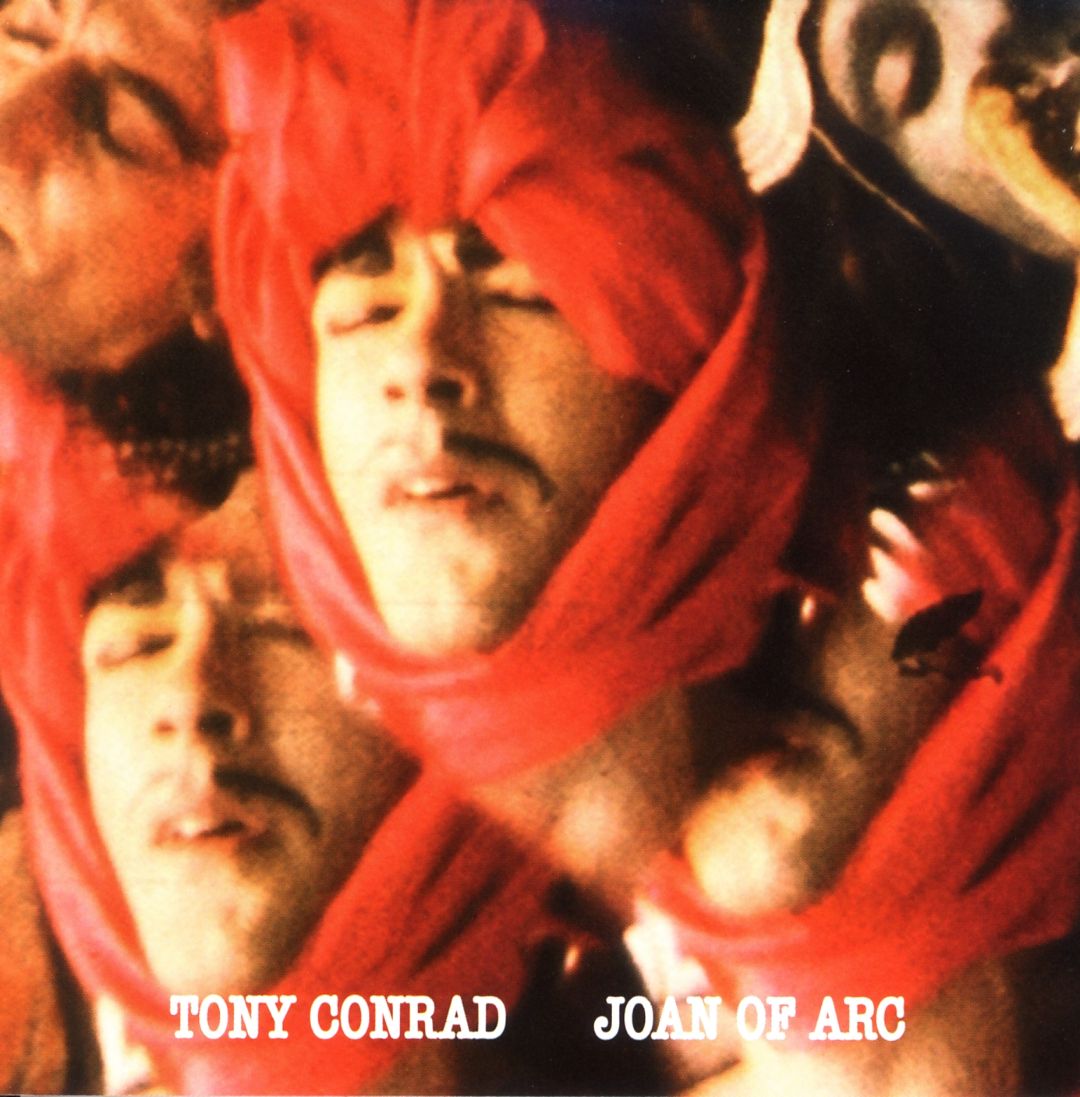

Tony Conrad Collection no. 16)

Tony Conrad

Joan of Arc (1968)

2006

Table of the Elements

[Iridium] TOE-CD-77

Compact disc

Tony Conrad is a founding father of "minimalism" and a giant in the American soundscape. With help from Table of the Elements, Conrad's Audio ArtKive imprint continues to document the wild breadth of his 40-year career, with an array of releases that includes field recordings, piano compositions, power electronics and more.

The indefatigable Conrad kept busy during the Revolution Summer of 1968. In addition to his reunion recordings with John Cale (documented earlier this year in the Cale set "New York in the 1960s"), Conrad starred in Ira Cohen's legendary film "The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda" and made extensive solo recordings, including Joan of Arc, available here for the first time. One of Conrad's personal favorites, it's a long piece for pump organ, in which he conjures both searing white heat and malignant gothic dread. An excerpt was used as the soundtrack for the Piero Heliczer film of the same name, but Conrad feels a greater affinity with that year's Cohen film; accordingly, Cohen graciously provided restored stills from "Thunderbolt Pagoda" for the packaging of this release. Cohen's sumptuous imagery—which Jimi Hendrix described as "looking through butterfly wings"—features a blissed-out and shirtless Conrad replete in pencil mustache, mascara and blood-red turban. The man is just downright cool—about as cool as Hendrix, and almost always louder.

“To anyone familiar with Tony Conrad's best-known works, Outside the Dream Syndicate and Four Violins (1964), mention of his name conjures a vivid sound: The drone of a bow slowly sawing across violin strings. Not that his other achievements—vital roles in the early minimalism of the Dream Syndicate, the early incarnations of the Velvet Underground, and the early experiments of American cinema—aren't equally memorable. But it's hard to picture him without a violin in his hands.

“Recent archival releases on Table of the Elements are changing that perception, offering examples of Conrad's work with sine-wave oscillation (Fantastic Glissando) and audio vérité (Bryant Park Moratorium Rally). Joan of Arc is the most exciting recovery yet, a solo pump-organ improvisation created to accompany Piero Heliczer's film of the same name. Conrad recorded the piece in 1968 at the home of John Vaccaro, director of New York's notorious Playhouse of the Ridiculous. Not knowing how much music Heliczer would need, Conrad played Vaccaro's aging instrument for the entire length of a one-hour reel-to-reel tape. (Heliczer ultimately used an excerpt for his 11-minute film.)

“As a display of energy and focus over an hour of unscripted time, Joan of Arc is simply impressive. Even more striking is how recognizable the piece turns out to be. On the surface, the pump-organ's low, moaning timbres, blurred by Conrad's lo-fi recording, share little with his violin's attacking treble. Rather than aggressive or sharp, his tone here is plaintive and often hymn-like. But the distinctive way he builds a drone, patiently layering and shifting it like wind and gravity shaping ocean waves, is unmistakable.

“The result is an entrancing meditation that rivals the work of latter-day masters Charlemagne Palestine and Phill Niblock, as well as the post-rock ambience of Stars of the Lid and Flying Saucer Attack and the metal dirges of Sunn0))) and Earth. What sets Joan of Arc apart is its all-alone aura. Drones often engulf their surroundings like a blinding snowstorm, but instead of evoking cold, dark landscapes, Joan of Arc feels warmly intimate, like crackling wood in a fireplace.

“Among all the sounds one might expect here—church-organ hums, cinematic chords, woozy groans—lies a surprise: an odd kind of percussion. Conrad's mic registers his foot tapping on pedals and his fingers clicking keys, creating rhythmic sparks and ripples beneath his cycling drone. As the organ swells and shrinks, these tactile sounds keep the piece grounded. Conrad's long chords may blow your mind, but his tangible effort makes Joan of Arc a dream come to life.”

Marc Masters, Pitchfork

“All right! New Tony Conrad! It's a good year. And there's (supposed to be, at least) a new Pandit Pran Nath disc on its way to my homestead as I type this! So despite what may be La Monte Young's best efforts, some of this music is making its way to the people. Just kidding La Monte (I can't afford a lawsuit). Of course this new Tony Conrad isn't really NEW new Tony Conrad, it's just never-before-heard Tony Conrad which is just as good (better?) as far as I'm concerned. "Joan of Arc" was recorded in 1968 as the soundtrack to a Piero Helicer movie of the same name which seems to be permanently AWOL, at least to the best of my knowledge.. It's a solo pump organ improvisation lasting 64 sweet minutes and is accompanied - as you can see on the cover - by stills from Ira Cohean's '68 film Invasion of the Thunderbolt Pagoda, which I also hope makes it to my doorstep someday

“It's difficult to come up with very many things to say about such a single-minded release, so I'll try and keep it short without being too verbose. There are a few things which jump to my mind at least a quarter of the way into "Joan of Arc", the first of which is the juxtaposition Conrad creates (however intentional) between the searing white pitch of the instrument and the brooding darkened tones which eventually take over almost completely. It's like listening to moonlight, if you can dig that. Like curling up on the grass in a field and letting luminous beams flood into your ear. But just as their is a juxtaposition with the result of the keys Conrad plays, there's also one audible in the grander scheme of the recording - not only can you heard the organ's final output but you can also hear the sounds it takes together. For example, Conrad's foot on the pump organ pedal often evoke a rhythmic spirit in the organ's drones that you didn't know were there until you heard the methods used to conjure them up. And then it all locked into place in your head until the foot-tapping went inaudible again and you were left to find your way once more.

“The composer's fingers also play the role of spectral tour guide, dancing around and sounding a bit like small rocks dropped into vast oceans, but they don't stay for long either. Of these external factors, however, the biggest compliment to "Joan of Arc"'s sound is the lo-fi tape recording it was committed too...it doesn't sound at all cleaned up and that's the way it should be. Apparently Conrad considers "Joan of Arc" one of his favorite pieces and I can understand why he'd be hesitant to alter it at all, even in the slightest way. I don't know if I prefer "Joan of Arc" to the violin works I've heard from Conrad...it's certainly a bit less...high strung? No pun intended, it just comes off a lot more mellowed, but of course that's the nature of the chosen instrument. If you like Charlemagne Palestine's organ drones, you should know where you're heading with this one and you know you're going to love it just like I did. Plus, the Con-man's stuff isn't always readily available at bargain-bin prices, but this one is as cheap as any other respectable CD you'll find and well worth the investment. Here's hoping Conrad's Audio ArtKive imprint provides many many more goods in the near future.

“It's so easy to call any kind of drone music boring, just out of reflex if for nothing else. But when you truly listen to a record like "Joan of Arc", the opposite becomes true - it provides an hour's worth of entirely stimulating, intriguing, organic music. And if you can't hear that, well I just plain feel sorry for you. Put it on your stereo, turn it up loud, and never fall asleep.”

Outer Space Gamelan

Tony Conrad Collection nos. 17) 18)

Jack Smith

Les Evening Gowns Damneés:

56 Ludlow Street 1962–1964, Volume I

1997

Tony Conrad’s Audio artKive/

Table of the Elements

[Palladium] TOE-CD-46

Compact disc

Jack Smith

Silent Shadows on Cinemaroc Island:

56 Ludlow Street 1962–1964, Volume II

1998

Tony Conrad’s Audio artKive/

Table of the Elements

[Silver] TOE-CD-47

Compact disc

Tony Conrad's Audio ArtKive presents the first two volumes in a series of remarkable vintage recordings which feature the protean film-maker, photographer and performance artist Jack Smith (1932-1989). The material includes readings of short stories and other audio excursions (featuring musical accompaniment from the likes of Conrad, John Cale and Angus MacLise), as well as excerpts from Conrad's soundtrack to Smith's notorious and groundbreaking film Flaming Creatures (1962). Recorded in glistening monaural lo-fidelity at Conrad's 56 Ludlow Street studio between 1962—1964, these pieces reveal an important facet of Smith's artistic legacy, and offer a rare glimpse at one of that decade's most influential milieu.

"More than almost any artist of the last century Jack Smith understood that within the prevailing cultures of success, art’s greatest role may have been to provide provision for public failure. To this end his actors and accomplices, props and lighting, drugs and desires were invariably wrong: wrong before the performance had started – before even the lights had gone down. The marathon of tourettic revisions, false starts and delays signaled to the world the impossibility of creating anything of value in a rectilinear lagoon where even the dedicated and willing were dragged to the bottom-feeding level of landlords and lobsters. Yet out of these impossible conditions was born the stuff of exquisite beauty, radical politics, lurid, caustic, pornographic and often hilarious evocations of the sexual and social strata in which we find ourselves. Much of this endures even in conditions Smith would have most likely have loathed. But the fact that the same frictions that heated and formed his work continue to frustrate curators as well as inflame and inspire artists – including those who have agreed to continue the spirit and legacy with works created for this show - is, I hope, testament to the enduring power and influence of Jack Smith’s extraordinary art."

Neville Wakefield

"Brilliant is an overused word, but it is the only one that will do for Smith. He was a difficult man who made an art of radical absurdity, one that recasts notions of beauty and authenticity in a new language — pansexual, by most lights grotesque — without abandoning the core concepts themselves. ... And he lived more or less the life he preached — a cross between agent provocateur and struggling student — to the end of his days.

"This isn't a model with much cachet at the moment. Maybe the streets have become too mean, or too soft to encourage it. Art schools turn out professionals; art itself often comes bite-size and neat as a pin. But Smith's work was the opposite of that. For him, one suspects, art wasn't bigger or smaller than life; it was life — messy, silly, awful, grand and above all transformative."

Holland Cotter, New York Times

"I genuflect before Jack Smith, the only true 'underground' film-maker."

John Waters

"He was uncompromising. He had everything."

Robert Wilson

"Gadfly, trickster, visionary — Jack Smith changed the art world. In wht seems like tamer times, it's great to look back at a genuine and truly out-there revolutionary."

Laurie Anderson

Tony Conrad Collection no. 19)

Pauline Oliveros

Primordial/Lift

2000

Table of the Elements

[Iodine] TOE-CD-53

Compact disc

Minimalist composer and founding member of the Deep Listening Band, Pauline Oliveros is known for creating pulsating soundscapes and sonic meditations. In these premier recordings, however, she engages a more aggressive, electric sound with assistance from Anne Bourne, Andrew Deutsch, Scott Olson, fellow minimalists Tony Conrad and Alex Gelencser, and Gastr Del Sol's David Grubbs. Within a strategic modulation processed through a low-frequency oscillator, Conrad's violin, Grubbs' harmonium, and Oliveros' signature accordion drone and enthrall.

“The guiding metaphor of Primordial Lift structures the musicians' performances, mirroring the resonate frequency of the earth and its acceleration from 7.8 to 13hz and beyond. In 1994 the frequency was already at 8.6 and 13hz will be achieved by 2010, at which point the magnetic fields of the earth will pass through a zero point and a polar shift will occur. The acceleration from 7.8 to 13hz is 'Primordial'; 13hz and beyond is 'Lift.'"

P.O.

"On some level, music, sound consciousness and religion are all one, and Ms. Oliveros would seem to be very close to that level."

New York Times

"What I had first learned about John Cale was that he had written a piece which pushed a piano down a mine shaft. We hungered for music almost seething beyond control — or even something beyond music, a violent feeling of soaring unstoppably, powered by immense angular machinery across abrupt and torrential seas of pounding blood."

Tony Conrad Collection no.10

John Cale

New York in the 1960s

2004

Table of the Elements

[Francium] TOE-LP-87

5x phono LPs, wood case, lacquer, silkscreen, dyed-linen libretto

John Cale

Tony Conrad

Angus MacLise

La Monte Young

Marian Zazeela

Day of Niagara: Inside the Dream Syndicate Vol. I

2000

Table of the Elements

[Tungsten] TOE-CD-74

Compact disc

Tony Conrad Collection no. 20

John Cale

Sun Blindness Music

2001

Table of the Elements

[Rhenium] TOE-CD-75

Compact disc, obi + catalog

Tony Conrad Collection no. 21

John Cale

Dream Interpretation: Inside the Dream Syndicate Vol. II

2001

Table of the Elements

[Gold] TOE-CD-79

Compact disc, obi + catalog

Tony Conrad Collection no. 22

John Cale

Stainless Gamelan: Inside the Dream Syndicate Vol. III

2002

Table of the Elements

[Mercury] TOE-CD-80

Compact disc, obi + catalog

Tony Conrad Collection no. 23

John Cale

New York in the 1960s

2004

Table of the Elements

[Francium] TOE-LP-87

5x phono LPs, wood case, lacquer, silkscreen, dyed-linen libretto

Tony Conrad Collection no. 24

John Cale

New York in the 1960s

2005

Table of the Elements

[Francium] TOE-CD-87

3x compact discs, wood case, lacquer, silkscreen, dyed-linen booklet

John Cale's great credit, both inside and outside the Velvet Underground, was to have found the inoculation dosage that would addict the music industry to SOUND without alienating one world from the other. But outside the "official" VU there was also an uncut version of the virus, incubated behind the slum walls of the 1960s Lower East Side, and maintained live in the liquid nitrogen of these insolently recorded reel-to-reel audiotapes, recorded and produced by Tony Conrad and now available in the massive Table of the Elements 3xCD (5xLP) boxed set, "New York in the 1960s."

"The recordings in this three-disc series come from another underground, a deep vein of labor and experimentation that parallels Cale's time with the Velvets. It is jubilantly private music, made alone and with like-minded spirits—Tony Conrad, Sterling Morrison, original Velvets percussionist Angus MacLise—far from the hot light of the Velvets' public notoriety and the rough politics of Cale's relationship with Reed. And it is important music, an illuminating, heretofore unknown chapter in Cale's creative advance.

"What is truly extraordinary about the sixteen performances spread across these three volumes—Sun Blindness Music, Dream Interpretation and Stainless Gamelan—is their explosive foresight. The florid distortion of Cale's guitar pieces and the tandem bull-elephant hum of his viola and Conrad's violin prefigure the aggressive majesty and expressive dissonance of punk rock, No Wave and the Transfigured Guitar movement led by Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham and Sonic Youth. In his pulsing keyboard essays, Cale marries the grace and science of minimalism to the mainstream throb of rock & roll, a full decade ahead of Brian Eno and the Berlin-era David Bowie. When Cale tests the barriers of possibility in his tools—the guts of an abandoned piano, the jammed keys on an organ, the pause control of a Wollensak tape recorder—he generates a synthetic music that connects Edgard Varése, Henry Cowell and Karlheinz Stockhausen with contemporary electronica and turntablism.

"These recordings have been virtually unheard since they were made more than three decades ago. But their prescience is undeniable. So is their power and purity. Working in the shadows of both pop and art, building on discoveries and inventions from his life before and with the Velvets, Cale committed to tape a highly personal and exhilarating vision of the future of music. It now sounds like fact."

David Fricke, from the liner notes

Earliest recordings by Velvet Underground founder and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member John Cale

Gorgeous, limited-edition release in black-lacquered wood box with black paper libretto

Liner notes by Rolling Stone's David Fricke

Features rare and previously unreleased recordings

Includes performances by fellow Velvet Underground members Sterling Morrison and Angus MacLise and minimalist pioneer Tony Conrad

5xLP set Includes bonus tracks featuring pioneering artist and filmmaker Jack Smith

"Shuddering rhythms at first sparkle like sunlight on water, before evoking the incandescence of a star going supernova. A reinvention of what we know of the past, and a treasure brought to light... Astonishing."

The Wire

"As devastating as the rock & roll on the Velvets' 'Sister Ray... Proves once again that La Monte Young's claim that he was the defining moment in minimalism is just insane."

All Music Guide

"These aural documents have been a long time in coming. They could have exploded the myth. Instead they are an awesome, concrete substantiation of all the excitement their long non-appearance has generated. They completely re-write the territory of minimalism with willful abandon and supercharged exhilaration. A revelation."

Monocular Times