“Anonymous Cleveland dude? This chord’s for you.”

Tony Conrad Collection no. 26)

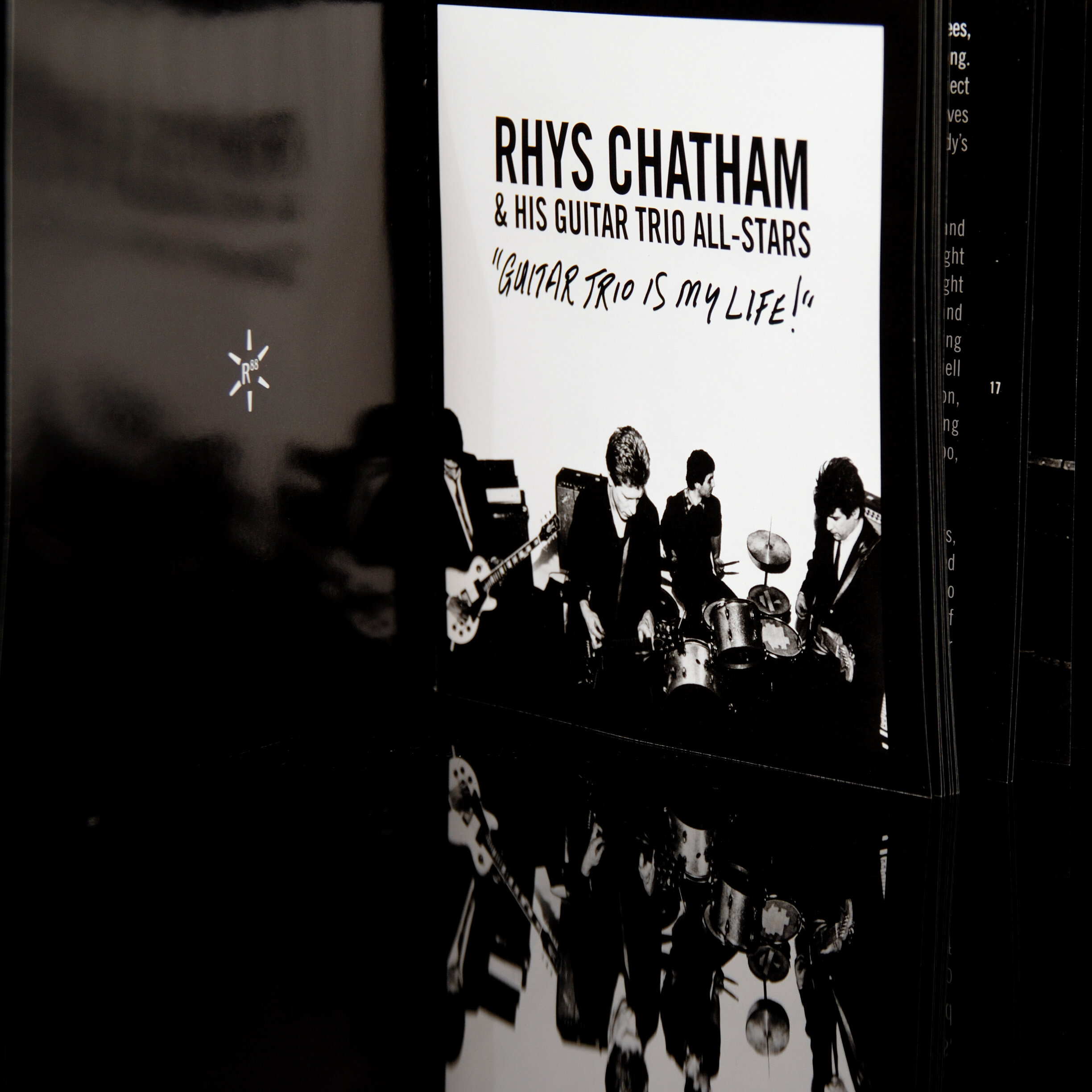

Rhys Chatham & His Guitar Trio All Stars

“GUITAR TRIO IS MY LIFE!”

2008

Radium/Table of the Elements

TOE-CD-813

3x compact discs, 48-page book

Utilizing multiple electric guitars and a single chord, 1977’s “Guitar Trio” is composer Rhys Chatham’s signature work, and a euphoric, minimal-punk classic. It’s an inspired amalgamation — the droning, shimmering harmonics of John Cale and Tony Conrad fused with the power and fury of the Ramones — that had a meteoric impact. It placed Chatham at the forefront of the burgeoning No Wave scene; its influence then spread further, as protégés and participants in Chatham’s ensembles — including Glenn Branca and members of Sonic Youth — folded the sound into their own. “Guitar Trio” remains a composition with a half-life, an adventure in sound that continues to radiate influence and inspiration.

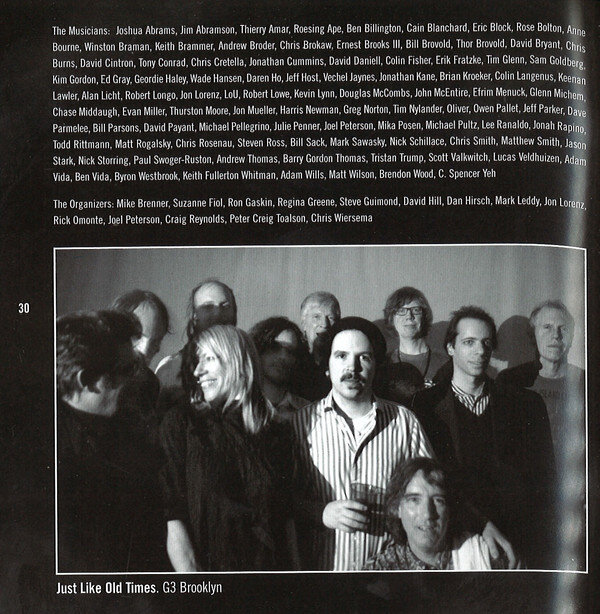

Now, to celebrate the 30th anniversary of “Guitar Trio” on an epic scale, Chatham musters an all-star guitar army for the 3xCD set, “GUITAR TRIO IS MY LIFE!” The sprawling collection features members of Sonic Youth, Swans, Tortoise, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Hüsker Dü, Modern Lovers, Silver Mt. Zion, Town and Country, Die Kreutzen, 90-Day Men, Collections of Colonies of Bees, and many more; even Tony Conrad gets in on the act. Together these artists celebrate Chatham’s wordless anthem, with its minimalist origins, rock & roll rhythm, ecstatic whorl of harmonics, and ever-evolving, ever-expanding nature.

So, take a listen, and hear what one man can do with hundreds of guitars, 30 years, one chord, and a skyscraper of amps set to Liquefy. “Guitar Trio” endures.

“[Rhys Chatham] is one of noise rock’s founding fathers. Without him, there would be no Sonic Youth, no Jesus and Mary Chain, no My Bloody Valentine … he remains a towering figure among six-string aficionados.”

Greg Kot, Chicago Tribune, author of Wilco: Learning How to Die

“Blue Oyster Cult and Kiss might’ve made noises about guitar armies, but it took composer Rhys Chatham to actually deploy one. And there’s no other way to say this: It rocks”

Bill Meyer, Magnet

“Surging phosphorescence … uplifting.”

David Fricke, Rolling Stone

“If you free yourself from the conventional reaction to a quantity like a million years, you free yourself a bit from the boundaries of human time. And then in a way you do not live at all, but in another way you live forever.”

John McPhee, Annals of the Former World

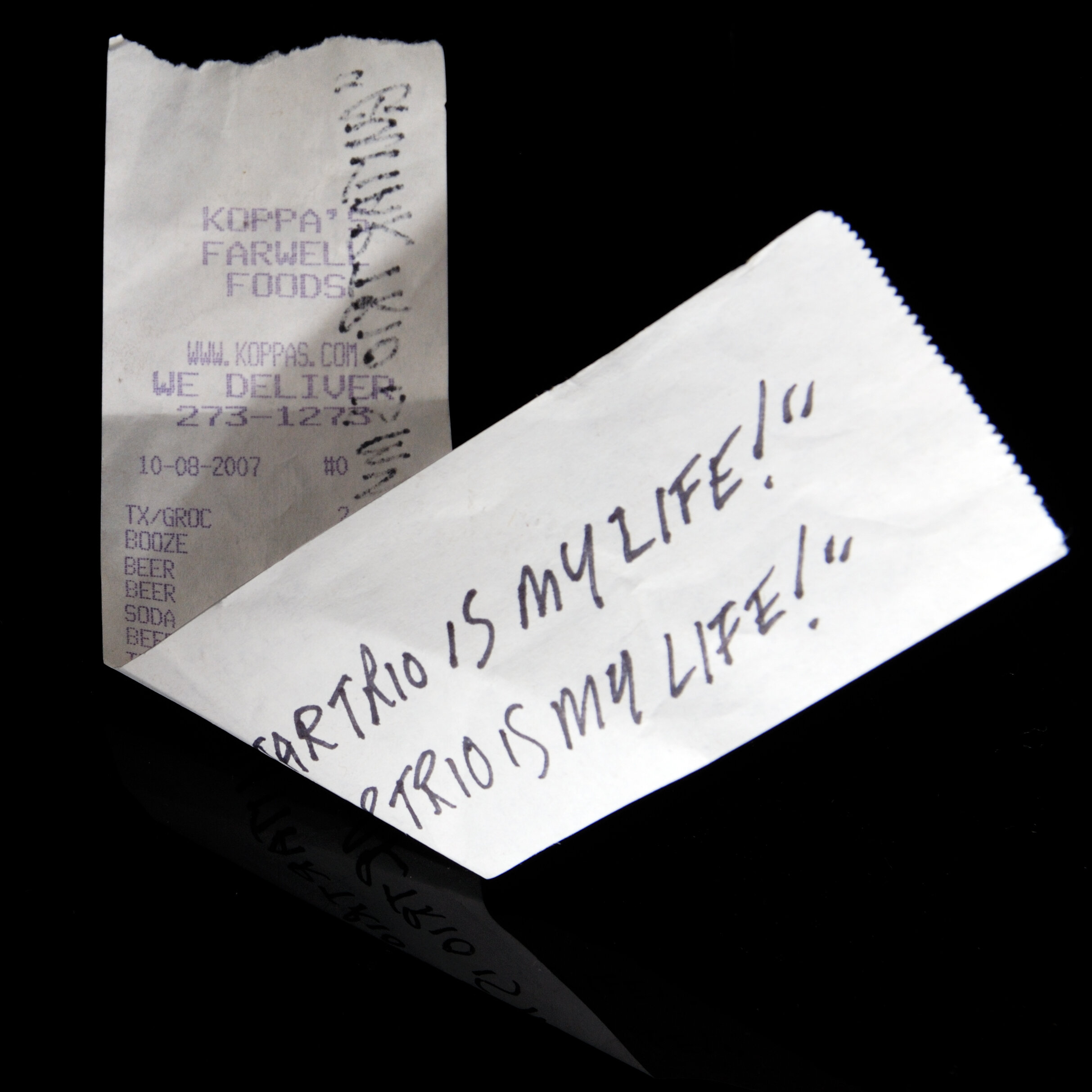

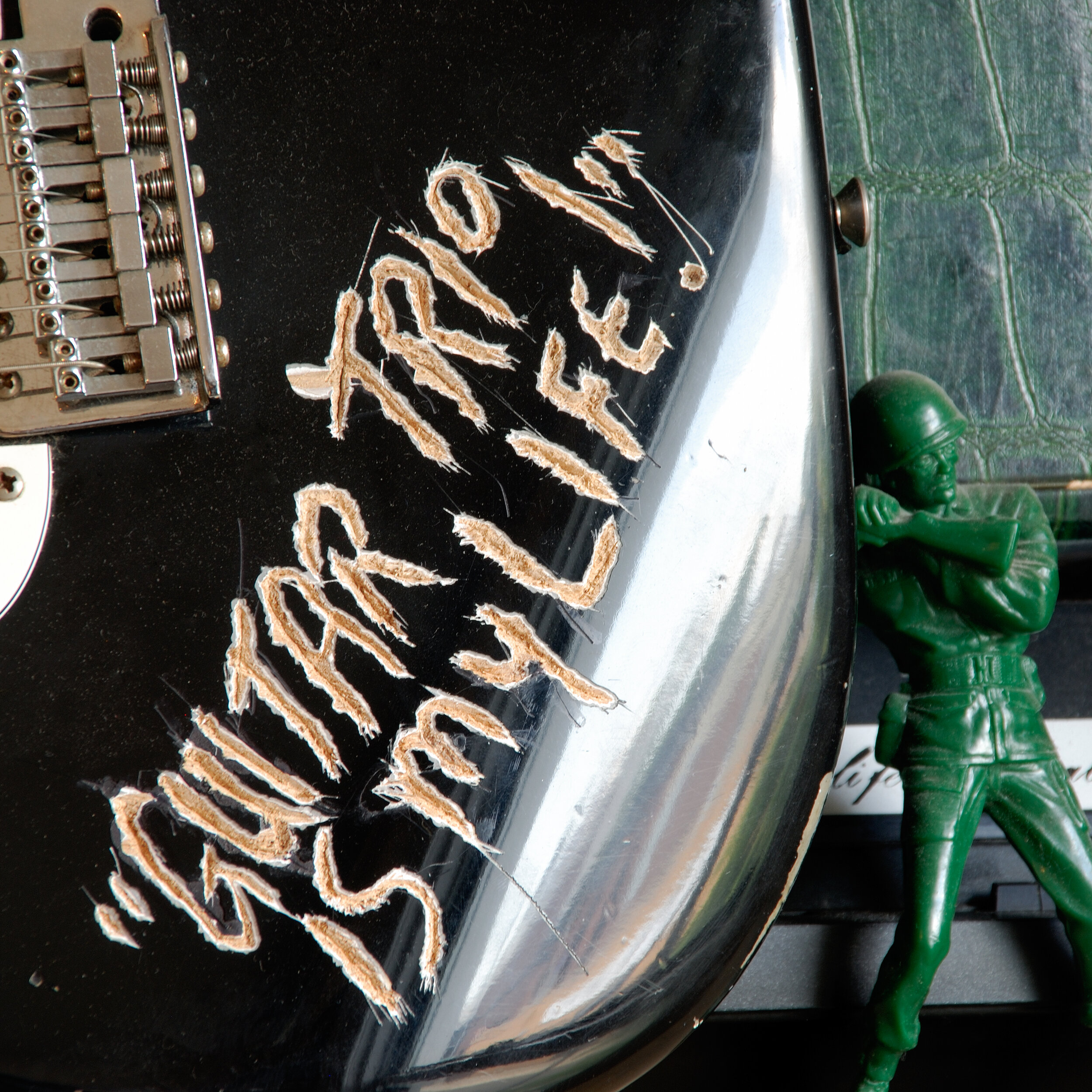

“GUITAR TRIO IS MY LIFE!”

That disarmingly concise personal manifesto was bellowed by a passionate, inebriated young fan at a 2006 Rhys Chatham concert in the de facto capital of rock ‘n’ roll, Cleveland. It pretty much says it all.

Written and first performed in 1977, “Guitar Trio” is, at first glance, a work for multiple electric guitars, all playing the same chord, E (well, Em7, if you want to get specific), with a special tuning of the strings, in a rhythm that vaguely resembles that of “My Baby Does the Hanky Panky” by 60s group Tommy James & the Shondells. Later versions incorporate more guitars, but the chord and rhythm remains the same. Yet Chatham’s signature work is much more than that; it’s a composition with a half-life, an adventure in sound that continues to radiate influence and inspiration 30 years after it was first performed in a New York nightclub.

Loud, raw, ecstatic New York minimalism has its source in the work of Tony Conrad and John Cale in the early 1960s. However, the original premiere of Rhys Chatham’s “Guitar Trio” is the point at which that river of sound jumped its banks and began to wind its way to the mainstream. At the time, the piece had an immediate impact; it placed Chatham at the forefront of the burgeoning No Wave scene, which blossomed in the fetid, fertile streets of the Lower East Side during the late 1970s. Its influence spread further, as protégés and members of Chatham’s ensembles folded the sound into their own. That sound continues to seep outward.

When Sonic Youth are inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (in Cleveland, of course—and you know it’s gonna happen), listen for some G3. It’s there.

* * * * *

Sound is physics, the building blocks, supplied courtesy of the Infinite Unknowable. Music is sound built up, folded back on itself; stacked, packed, arrayed, layered, spliced, diced, origamied, beaten, caressed, wowed and wooed. And sometimes, given sufficient inspiration, music gives way to song.

Rhys Chatham has spent a lifetime sailing a sea of electromagnetic waves. He has presented his work on the steps of, and beneath the immense dome of, the basilica Sacre Coeur, one of the most prominent landmarks in Paris, conducting a choir of 400 electric guitars; he has performed, with a slightly more manageable ensemble of nine, in the humid environs of Shreveport, Louisiana, beneath the patined gaze of the ghosts of Hank Williams and Elvis Presley. He was equally at home in both locales.

Chatham was born in 1952 in Manhattan. A prodigy, he began playing the harpsichord at age 6; by his teens he was studying composition, first with electronic composer Morton Subotnic; then with minimalist La Monte Young. He was also to come into the elliptical orbit of the polymathic trickster, Tony Conrad.

Plenty has been written about the rift between the latter two, former collaborators whose subsequent aesthetic and philosophical paths would take them in directions of polar opposition. Young sought to establish a kingdom of aural and mathematical perfection; while Conrad, the creator of a highly precise performance idiom of his own, was tolerant of error, at ease with noise and grit, and enamored of mind-crushingly high volume. He also possessed an arch, mischievous sense of humor. Count Conrad as one influence on “Guitar Trio.”

During this period, Chatham’s greatest influence may have been his day job—and vice versa. In 1971, at the age of 19, he became the first music director at The Kitchen, in Greenwich Village. Originally intended as a space for the installation of video art, its curatorial mission soon expanded to include various other media, including live music. Under Chatham’s direction, The Kitchen became the great sound incubator in 1970s New York, and the list of musicians, artists and performance artists who got their start there is vast. Laurie Anderson, Cindy Sherman, Eric Bogosian, Philip Glass, Peter Greenaway and Brian Eno all passed through its doors; many of them at Rhys’s invite; all of them under the influence of his tenure. Ironically (or shrewdly), he was largely responsible for creating the scene that would soon be rapturously embracing his own work.

Then it happened. The epiphany arrived in a black leather jacket. As Chatham recalls, “Prior to 1975 I was a minimalist composer. I did concerts lasting three hours, sometimes playing one single pitch or chord on voice or through electronic means.” But he had never been to a rock concert. Ever. So, on a breezy May evening in 1976, his buddy Peter Gordon, also a composer, decided it was high time that his pal lose his aural virginity. Gordon grabbed Rhys, and together they went to the most notorious sonic brothel that ever has been, or ever will be. Chatham walked beneath the awning and through the door at 315 Bowery towards his date with destiny—and what a hot date it was. He was at CBGB, and he was about to see the Ramones.

Tommy, Johnny, Joey, Dee Dee. It was the original line-up, the first record was about to come out, and they were tight. Chatham states, “What I heard at that Ramones concert changed my life. Those guys were playing three chords, which was two more chords than I was playing, but I felt a resonance with what they were doing; they struck a deep chord in my minimalist heart.” He acquired a Fender Stratocaster the next day.

It took a year to sufficiently master the guitar and completely articulate his ideas, but a year later Chatham, the minimalist turned punk rocker, hit the stage for his first show. His music was an amalgamation: intricate and visceral; rowdy and contemplative; aggressive yet also, with its emphasis on harmonics, strangely wondrous and inspiring. Even more bizarre, it was vaguely danceable. It made him an instant hit in the downtown scene. While CBGB hosted the first tier of punk/new wave bands, such as the Ramones, Blondie, Television, and the Talking Heads, Rhys would lead another, more experimental gang of artists that included Lydia Lunch, Mars, Liquid Liquid, and DNA. They called this art/rock “No Wave,” and even Eno took note. At the forefront was the remarkable “Guitar Trio.”

In early 1979, Rhys was unknowingly presented with an opportunity to pay forward a karmic debt. A young man, new to the city, was rifling through the Village Voice on a Tuesday night, looking for something to do. Seeing the ad for a Rhys Chatham gig, he and a buddy decided to check it out. It was Lee Ranaldo’s first show, and he was floored. Years later he would describe the experience.

“There was something going on that I couldn’t put my finger on. Although the players seemed to be simply strumming, amazing things were happening in the sound field above our heads. Overtones danced all around the notes, getting more and more animated, turning into first gamelan orchestras, and then a choir of voices, ping-ponging over the minimalist low notes of the rocking chord.”

Then, the piece concluded, and the crowd went nuts. You can imagine Lee’s shock, surprise, and glee when Chatham began the next number—the first one was long enough to be a set on its own, back in the punk days—and the band launched into the exact same thing. He also observes that Rhys was staggeringly high on a bizarre mélange of drugs. (It was the 70s. Who wasn’t?) Anyway. Lee concludes, “I had never heard anything like it before, yet I’d heard it in my head forever; finally here it was in front of me.”

The double performance of “Guitar Trio” that Lee and his buddy David Linton saw that night was essentially unchanged from the original that premiered almost two years earlier. The first version had a drummer, but playing only hi-hat cymbals; the second featured full drums, plus a slowly—very slowly—lap-dissolving series of blue-tinted slide projections. These depicted a skyscraper; a woman in a bouffant with child, both shielding their eyes while looking at the sky; a man running into an alley; a Japanese Zero flying low along the beach; Pennsylvania Station; a figure walking alongside a horse, carrying a prone toddler. Their meaning is opaque, cryptic; they’re somewhat iconic, and convey a subtle melancholia. They were specifically created for the piece by one of Rhys’s friends, an unknown, struggling artist named Robert Longo.

Longo also performed as a musician in one of Chatham’s many ensembles of the late 70s and early- to mid-80s. You can assess the vivid, compelling originality of Rhys’s work by the number of artists who met him, were taught his work, performed it, then carried its influence into groups of their own. Both David Linton and Lee Ranaldo joined Rhys’s ensemble. David stayed with Rhys for years, and remains a NYC fixture. Of course Lee co-founded Sonic Youth in 1981; bandmate Thurston Moore was also a Chatham veteran. Robert Poss and Susan Stenger went on to form Band of Susans. Jonathan Kane, who enlisted with Rhys in 1981, as the groups were starting to expand into guitar armies, has gone on to serious critical acclaim with his own group, February. Later in the 80s, Page Hamilton passed through before forming the hugely popular band Helmet. Glenn Branca, who was in one of Rhys’s earliest groups, went on to emulate the massed-guitar strategies and idiosyncratic tunings, with great solemnity. It’s all cool with Rhys. To quote the Temptations, funk era: “And the band played on.”

As the 80s progressed, Chatham added more and more guitars, and his compositions became increasingly elaborate, best showcased in the ebullient, 1985 classic, “Die Donnergotter.” In 1988, he left New York, following the future ex-Mrs. Chatham to Paris, where he remains today. From there he wrote “An Angel Moves Too Fast to See.” It’s a breathtakingly rich, varied work for 100 guitars, plus bass and drums, with the latter handled by Ernie Brooks (from the original Modern Lovers) and Jonathan Kane, respectively. Together they’ve toured “Angel” around the globe, teaching it to local guitarists, then presenting it in cities and towns from Scandinavia to Montreal to the tiny, actively volcanic island of Reunion, deep in the Indian Ocean, down Madagascar way.

After his self-imposed expatriation, it would be nearly 20 years before Rhys Chatham again played his guitar-based work in his native land. But at the 2005 premiere of his composition “A Crimson Grail,” commissioned by the city of Paris, and presented to a throng of thousands, he managed to slip in a version of “Guitar Trio.” It was played by 400 guitarists and viewed on national television throughout France.

It’s hard to keep a good tune down.

* * * * *

It’s 2007. Three decades have passed since the premiere of “Guitar Trio,” and things have come full circle. Literally. Rhys Chatham stands with his back against a curved wall in a round room; next to him is an amp; in his hands, a guitar. Positioned equidistance around the wall of this peculiar setting stand nine more guitarists, and a drummer. None of them could move away from that wall if they wanted—the room is packed with people. Outside, disappointed latecomers are turned away in droves.

As Rhys glances up, he makes eye contact with the various members of his ensemble, and in doing so, looks back in time. To his far left is Lee Ranaldo, reunited with Rhys after so many years, his tousled brown mop now completely white. That’s okay; Rhys’s bright red mane has undergone a similar transformation. Also in the circle are Lee’s bandmates in Sonic Youth, Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon. To his immediate right is Robert Longo. After his stint with Rhys, Longo went on to fame and fortune as one of the most acclaimed artists to emerge from the 1980s; he even directed feature films. But here he is, guitar slung low, wearing what looks to be the same black suit he wore on stage with Rhys 30 years ago, playing for beer like the rest. Long-time 80s and 90s lieutenants Ernie Books and Jonathan Kane are there, too, Ernie also going white.

There are also some younger faces, more recent initiates to the Chatham circle. David Daniell, Rhys’s new right-hand man is there; so is Daniell’s young friend Adam Wills. Wills is positioned next to Lee, and in many ways he mirrors him. As Lee was once, Adam is known only in New York, where he is known well, for his bass playing in Jonathan Kane’s band, and his guitar heroism in Bear in Heaven. He’s taking it all in stride, Lee on his left, Kim on his right. Maybe he’s scared witless, but you wouldn’t know by looking. Also present are Colin Langerius, from USA Is a Monster, Byron Westbrook, of Corridors, and the multi-talented author and composer Alan Licht. They fidget with gear.

The venue is an old oil silo set alongside the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. The entire legality of this event is dubious at best. The sole commode continues to disgorge its contents on to the floor. A few months ago, Rhys was performing inside the largest cathedral in France. This really is like old times, but no matter: It’s show time.

The lights dim. Jonathan counts off, the ritual invocation of rock. Rhys drops his hand, and he sounds that chord. It’s slightly sinister at first, alone, like a burglar sneaking into the room. Slowly, the others join in, one at a time, subtly, stealthily. The guitars and bass keep the rhythm. The volume increases, the tension turns slowly to joy. Harmonic overtones blossom in the air, every spare bit of oxygen rings like church bells. This being the first go-around, Jonathan is restricted to hi-hat. You can tell it’s killing him, but if he’s going to only play hi-hat, he’s going to play it like no one’s ever played it before. Metallic staccato beats zip around the room like bullets on Omaha Beach. Louder, louder, louder. Euphoria. One chord, 30 years. “Guitar Trio” lives.

This is the first show of a US tour. The tour is named “Guitar Trio Is My Life!” as a nod to that kid from Cleveland, and for the next few weeks it will snake its way through New England, Canada, and the Midwest. The band is trumpeted as “The Guitar Trio All-Stars,” but only Rhys and David Daniell are permanent members. The other nine musicians are recruited locally. Rhys will teach them the piece during sound check, then away they go. There will be some variance—in Toronto there will be even more guitar players, plus a string section—but mostly the arrangement will resemble that of New York.

The musicians are labeled “All-Stars,” and many of them will hail from prominent bands. Rhys will be joined by members of Tortoise, God Speed You Black Emperor, Husker Du, Brokeback, Lichens, Town and Country, Die Kruetzen, Bird Show and more; even Rhys’s old buddy Tony Conrad grabs an axe and gets in on the act. However just as many will not be bright lights in the indie-rock firmament; some will be guys and gals from local bands who will never make a record or achieve even relative, regional fame. However, for one night they’re all on stage together, wallowing in shimmering nebulae of sound, stars all.

Listening to recordings of the tour, it is remarkable to hear the variety in the performances. A composition comprised of a single chord? On paper it sounds like abject formalism, probably boring, and possibly an exercise in mild sadomasochism. In live performance, it is a wildly undulating ride, the guitars chafing at the bit, a galloping team ready to bolt, barely under rein. It is controlled chaos, and frankly has as much in common with free-improvisation as it does with minimalism. The inverted structure—the guitars are the rhythm section; the bass and drums run amok; above it all, the whorl of harmonics—guarantees an infinite variety of interpretations. Yet it always seems to work. It’s like Lee says. You can’t put your finger on it, but there’s something about it that speaks to you.

By now it’s a miracle that Jonathan hasn’t cracked the hi-hat cymbals. He’s a dervish, a blur, and the circle of guitarists is following his lead, having completely abandoned the original rhythm in order to play as fast as humanly possible. The crescendo complete, the musicians are no longer playing, but the air remains thick with sound. Cheers immediately follow.

As the applause begins to wane, the stage lights dim, and a luminous blue glow fills the room. A skyscraper appears. The applause doubles, quadruples. Jonathan counts down and Lee, reflecting back to a moment that so shocked and thrilled him decades earlier, once again summons The Chord.

The second version doubles the ferocity of the first. Now unleashed, Jonathan is an animal, a magnificent beast. Whatever self-doubt Adam might have had was unfounded; he rocks, as well as anyone in the group, possibly more. A light pours out of Rhys.

When it’s over, and the applause finally dissipates, everyone in the room recognizes they’ve participated in something special.

* * * * *

Music is as fundamentally Human as it gets. Since we first climbed out of the trees, it's been our mating call. Add language and you’ve got our collective codex: song. In song we express our fears and hopes; we share our lusts and desires; we project our anger and boast of our courage; we console each other, and we get ourselves riled up. We celebrate our God. We profess our loves. One way or another, everybody's got a song to sing.

There's a video clip making the rounds on YouTube. Check it out. It's Rhys and the G3 gang on stage in Milwaukee. It's the end of the last set, on the last night of the tour. The stage is enormous, the biggest of the tour by far, but tonight it's not nearly big enough for these guys. They are pummeling the piece, and the stage, and themselves: jumping, leaping, rolling on the ground, writhing on their backs; colliding, staggering, colliding again. Even bandleader Daniell drops his usually stern visage and joins in, laughing. It's maniacal abandon, a romp, and Rhys is right in the thick of it, dropping to his knees and rocking out with his guitar, just like Chuck Berry or Pete Townsend. The crowd, too, is ecstatic.

Rhys Chatham has spent his entire life in the company of musicians, writers, artists, dancers, and poets. They are drawn to him and he to them. He has crafted magnificent works that will outlive their creator, and a legacy that will continue to inspire others. While he wishes it were otherwise, he'll only be able to meet a few of the fans who pack the clubs and halls to see these shows. Yet when they stagger home, inspired, some of these kids will vow to make music on their own. A few of them will do it. And maybe one or two of them will immerse themselves in music for life. Like Rhys has.

No longer the teenage wunderkind who led the New York avant-garde into battle against the Hoards of the Age of Aquarius, this Rhys Chatham is 54, floating inexorably towards the far side of middle age. Presumably he endures the same bevy of mundane annoyances as other folks: medical issues, problematic relationships, unpaid bills; uncertainty, regret, malaise. Tonight, none of that exists. Look at his face. He's beaming. He's having a blast. Tonight, in Wisconsin, USA, Rhys Chatham is a rock star, and he knows it, and he's doing exactly what he wants to do.

Pause the clip.

What if we could intrude in the moment? Rhys Chatham has been devoted to a wordless anthem for 30 years. What is it, exactly, that “Guitar Trio” conveys so effectively, with its minimalist origins, rock & roll rhythm, shimmering, ecstatic harmonics, and fluid, ever-evolving, ever-expanding nature? Why does it resonate, generation after generation? What simple, human fundamental does this bit of music communicate about Rhys himself? What if we could go back to that night in Wisconsin, stop the clock as we have now, and ask him?

No need: Look at his face again. Bliss. There’s your answer, simple and obvious. Rhys Chatham is singing his song. “Guitar Trio” is a serenade, a love song to sound itself, from a man whose entire life has been a rhapsody, a bending and a blending of forms and genres. Losing himself within the embrace of sound is his passion, and with “Guitar Trio,” he allows you to share his infatuation, and indulge your own, too. See the exuberance in all those boys on stage, frozen in a mid-tumble blur of beard, denim, guitar, and western-wear shirttail? They’re also in love with sound. That’s okay; there’s plenty to go around.

Sound goes low, deep to the core of the Earth. It goes high, too: higher than we can tolerate, then higher than we can hear, then higher than any living creature can hear. It goes higher and higher and higher still, until it rains down as sunlight and collects in pools as all the colors of the spectrum. Feel lucky? Reach out and grab just enough to make a single chord. Who knows? It might even be enough for a song.

* * * * *

So there you go. Take a listen, and hear what one man can do with hundreds of guitars, thirty years, one chord, and a skyscraper of amps set to "Liquefy."

"Guitar Trio" endures.

Oh, and go ahead, hit Play, and watch the rest of that YouTube clip. As with life in general, the quality sometimes sucks, but it's the spirit of the thing that matters.

One more thing. Anonymous Cleveland dude?

This chord's for you.

Jeff Hunt

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

August 2007

If the most pure rock'n'roll is all about excess, emancipation, and sexuality, then 55-year-old Parisian composer Rhys Chatham makes Mick Jagger seem like a Sunday school teacher: Chatham's second 3xCD box set for Table of the Elements, Guitar Trio is My Life!, collects 10 performances from Chatham's 2007 14-city North American tour. Every night, Chatham and a different ensemble of musicians performed his most famous work, 1977's "Guitar Trio", twice. It's about time: For too long, Chatham's massed guitars have been a footnote to those of the more famous Glenn Branca. But Branca--- like Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo and Thurston Moore, Swans' Michael Gira and Jonathan Kane, and the Modern Lovers' Ernie Brooks, many of whom appear here-- was an early student of and member in Chatham's New York ensembles. This exhausting, exhilarating collection, though, should confirm both Chatham and "Guitar Trio" as staples in the rock and 20th cenury composition canons. At the very least, from the first E note to the last E chord three hours later, it proves that Chatham-- also significant for his curatorial role at New York's The Kitchen in the 70s and in the establishment of No Wave later that decade-- fucking rocks.

The "Guitar Trio" score is deceptively simple: "In this century, it has never taken more than an hour to teach 'Guitar Trio' to everyone's satisfaction and comfort level," Chatham wrote in the score notes circulated for the 2007 tour documented by Guitar Trio Is My Life! "So please don't worry about anything." Several guitar players gather around a drummer and an electric bassist. Their amps are clean, loud, and high on treble. The drummer counts off, and Chatham strums an open low E string, his rhythm a bit like a jumpy 60s Brit Invasion tune. The drummer plays a cantering, steady rhythm restricted to the hi-hat. One by one, Chatham signals each guitarist to join. The bassist enters. After several minutes, Chatham begins strumming the top three strings and then signals each guitarist to do the same. Later, Chatham begins strumming all six strings, fretting only the second string to B. Eventually everyone stops playing except the drummer, still using only hi-hat, and Chatham, again playing one string. The entire process repeats, and it's generally a bit briefer the second time around. The music fades out with a final chord played on a conclusive downbeat. Chatham announces the ensemble, bows, turns to his band, and starts again in the exact same way. Except this time, the drummer is given use of his full kit, especially the snare and kick drums. The only previous version of "Guitar Trio" (available on the long-since out-of-print 2002 box set An Angel Moves Too Fast to See and on the 2006 disc Die Donnergötter) was eight minutes long (first cycle only). The shortest take on Guitar Trio Is My Life! is the second Brooklyn cycle, which ends after 16 driving minutes.

But the "Guitar Trio" sound is surprisingly dynamic: Chatham does not specify when any given player should play above any given fret or for what length of time. Such inherent indeterminacy means that what begins as a stately, strummed guitar pattern begins to mutate and grow into surprising shapes. This variety of sounds builds cumulatively into a thick swath of high and low overtones bouncing off of each other like long-lost kin at a crowded family reunion. All of the sounds are made from the same E string or E chord, but none of them are exactly the same. By the time "Guitar Trio" hits its six-string segment, it's as thick as a furious blizzard. When the notes really come down, it's beautiful and overwhelming.

Still, 10 versions of the same 16-to-30 minute piece of music? Boring, right? Perhaps were it not for the musicians included here-- from members of Tortoise, Sonic Youth, and Thee Silver Mt. Zion to an unknown but incredible Buffalo drummer named Jim Abramson, who gloriously mauls his 21 minutes of Table of the Elements time on Disc One. "Guitar Trio" ingests individual talents and funnels them into a composition loose enough for new ideas but tough enough to test physical and mental limits: On the full-drum version from Toronto, then, you get a six-piece string section (including Final Fantasy's Owen Pallet), thickening the guitar sound into a viscous smear. But after the one-string turnaround, it sounds like Chatham's worn them out. Same for Tortoise's John McEntire, who turns in the best brass-only drumming with his Chicago performance, riding his hi-hat with impeccable time and finesse. But he gets lost inside the nine-guitar storm on the full-kit version, unlike improvisational heavyweight and Collections of Colonies of Bees drummer Jon Mueller. Like he does on this year's solo drum Table of the Elements release Metals, Mueller rattles speakers from the frame. His kick drum and heavy snare slap fearlessly. They lash at the six guitars like the only way out is revenge. Same for Ernie Brooks' bristling bass pops on the second set from Brooklyn: With a rhythmic sense that sounds like whiplash must feel, he folds his own aesthetic beneath Chatham's masterful umbrella work.

When considered alongside Chatham's statement that he can teach anyone this piece in an hour, such variety is exhilarating. "Guitar Trio" was composed after Chatham, then a New York composer taking a somewhat academic approach to minimalism, saw the Ramones play CBGB. Their music shocked him into redirecting his sonic approach within his own pre-existing ideas. The result is glorious, one-chord, electro-orchestral, garage-band minimalism. Anyone can learn this music. Anyone can play this music. Anyone can enjoy this music, rhythmically and tonally electrified as it is. This is a popular inroad for both understanding and participating in sound fields generally relegated to academia. "Guitar Trio" suggests infinite possibilities for this music, for all music, really: If you can combine basic "punk" ideas with basic "classical" ideas to create something that will forever alter the shape of both memes (see Sonic Youth and Glenn Branca), what can't you do?

Grayson Currin

Pitchfork Media