Keith Rowe

City Music for Electric Guitar/

“We Want Some Minutes, Okay?”

Guitar Series Vol. I

1993

Table of the Elements

[Boron] TOE-SS-5

7” single

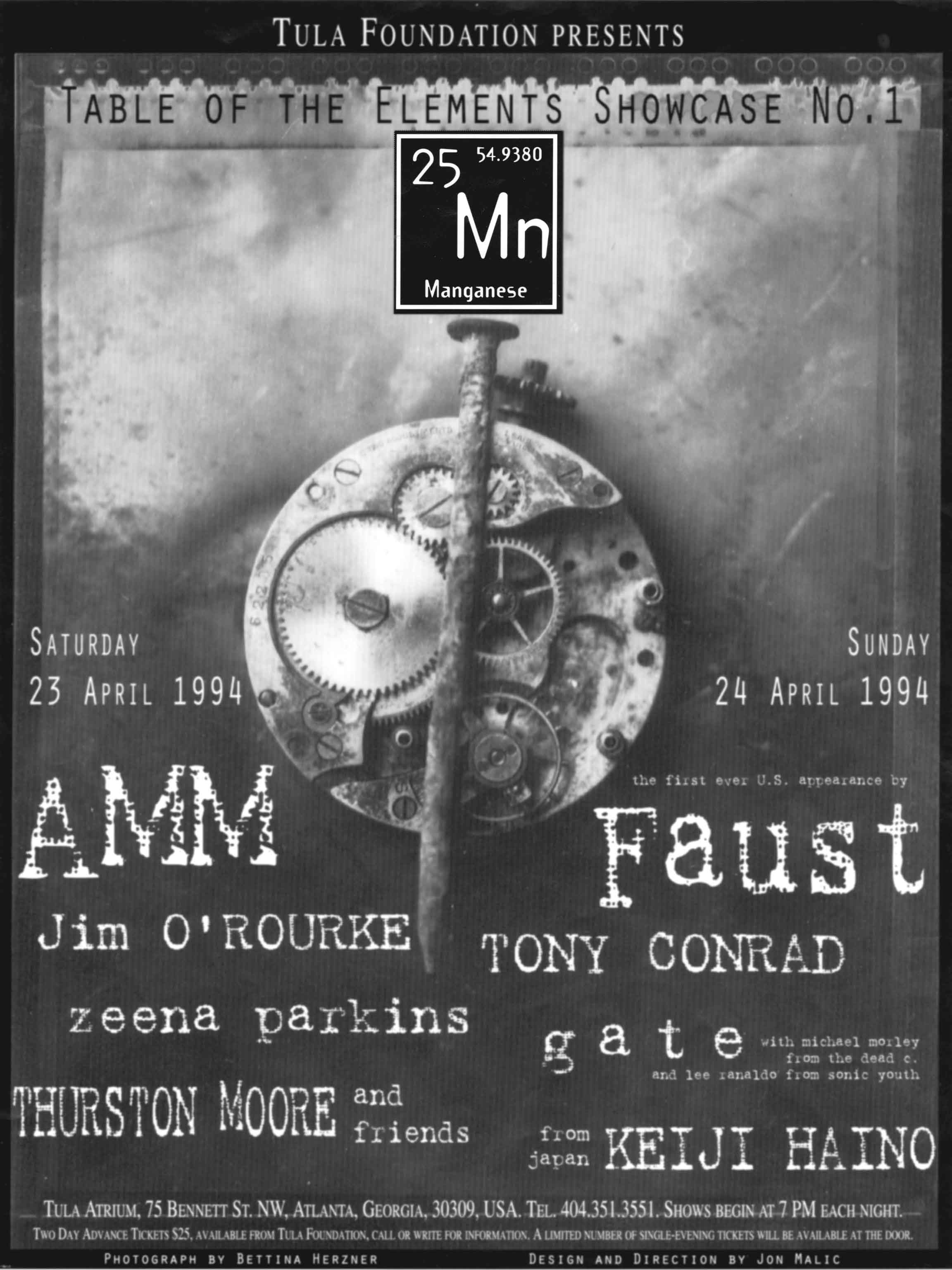

AMM (UK)

Tony Conrad (USA)

Faust (Germany, First US appearance)

Gate (New Zealand)

w/ Michael Morley + Lee Ranaldo, Thurston Moore, Steve Shelley

Keiji Haino (Japan)

Thurston Moore and Friends (USA)

w/ Thurston Moore + Tim Foljahn, Steve Shelley

Zeena Parkins (USA)

Jim O’Rourke (USA)

Manganese

Table of the Elements Festival no. 1

Table of the Elements

Tula Foundation

April 23—April 24

1994

[Manganese] TOE-25

Tula Atrium (Georgia Museum of Contemporary Art)

75 Bennett St. NW

Atlanta, Georgia

Two-day tickets: $25.00

Producers: Jeff Hunt and Kris Johnson

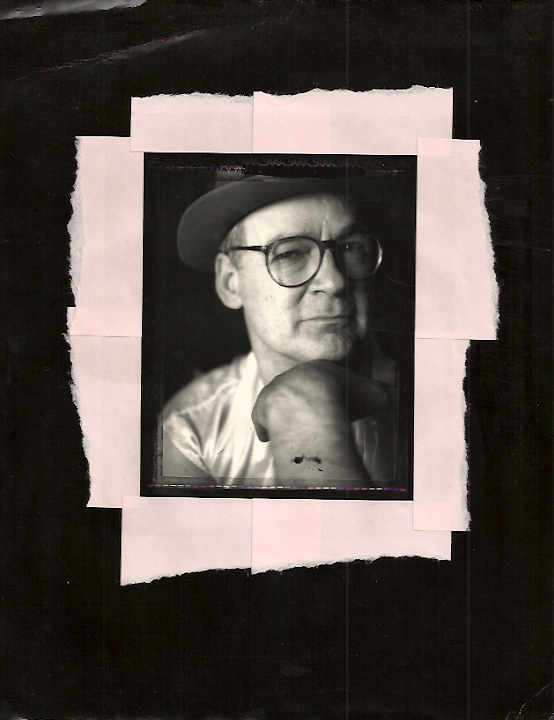

It's easy enough to make romantic claims for an artist like Tony Conrad. He's one of those guys. Ur-Sixties. Quintessential cult figure. Resident outsider. Rebel angel. The minimalist who came in from the cold. He's got the kind of immaculate credibility that can't be bought and can't be sold. [And how else, otherwise, could he have persevered?] Rumbling under the cultural radar since the Kennedy Era, Conrad is at once first cause and last laugh, a covert operative who can stand as a primary influence over succeeding generations, while pretty much conducting most of his business in obscurity. That is, until about 10 years ago, when the Table of the Elements label finally blew his cover for good. And because he'd kept such a low profile, when Conrad did pop up, the impression made was a good deal more spectacular by sheer dint of surprise. Who, exactly, was this guy? It was an unusual weekend in Atlanta, Georgia, when people began to ask—again. Conrad was having one of his first "coming out" parties, and despite some of the odd circumstances, it could not have been staged more memorably. The Manganese Festival, which doubled as a kind of avant-garde debutante ball for Table of the Elements, went down April 23 and 24, 1994, at the exact same time as Freaknik, the "spring break" for students from the circuit of predominantly black colleges. Atlanta became an urban version of Daytona Beach for three days, with traffic grid locked, boom boxes shouting, and provocatively ample derriere-shaking for mile after mile along Peachtree Street—the main stem that runs into the heart of "The City Too Busy To Hate." The festival was sequestered in a complex of art galleries off an industrial side street intersecting Peachtree (and thus, cut off in such a way that anyone who managed to drive in could not possibly hope to drive back out until the traffic jam subsided many, many hours later). This was ideal, for anyone hoping to maximize the singular nature of the experience. You could check out any time you liked, but you could never leave. Perfect for a first encounter with Tony Conrad. He cut a curious figure, Tony did, in his bowler hat and his shorts, prowling the premises with a video camera, documenting the goings-on as if at some family reunion. In a sense, it was: The gathering tribes included Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo and Steve Shelley from Sonic Youth, electric harpist extraordinare Zeena Parkins, avenging Japanese guitar hero Keiji Haino, the anarchic artistes of Faust—Conrad's long-ago collaborators on "Outside the Dream Syndicate"—and the then-unknown, now-ubiquitous wonder boy Jim O'Rourke. Pioneering British improv trio AMM was in the house, as was New Zealand's rare-to-such-shores Gate. This was an unusual assortment of performers, a Lollapalooza for fringe-dwellers, and a model for further electrical storms—such as the All Tomorrow's Parties festival—that would light up the skies into the new millennium. By the time Conrad finally came to perform, sandwiched between the jet-engine decibel bath of Haino and the ritualized freak-out of Faust, even those not in the know were primed for a paradigm shift. The city was in a gridlock, as surely as if suffering a collective panic attack or celebrating a coup d'etat. What better moment to pump up the volume, and tune in to those strange frequencies.

Excerpt from “Tony Rocks”

Steve Dollar

New York City

March, 2003

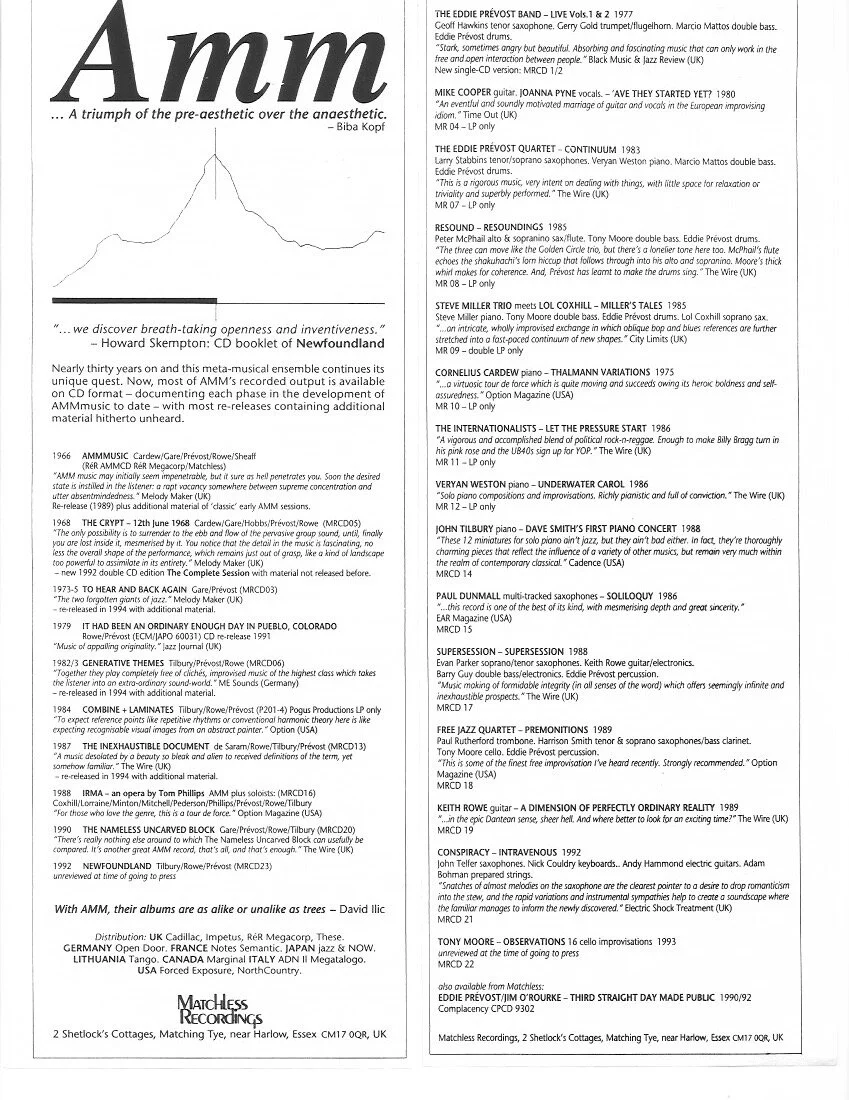

"The first recording by these pioneers of electro-acoustic improvisation, AMMMusic stands the test of time both as a remarkably prescient session and as an utterly powerful and deep piece of 20th century music. Drummer Eddie Prevost's superb and detailed liner notes document AMM's early history, including the confusion engendered not only in audiences and critics but even in the band members themselves, unsure if they were in a free jazz ensemble, a contemporary classical group, neither, or both. The aphorisms adorning the original LP issue (the disc includes additional portions of the concert) give some indication of what was facing listeners and musicians at the time: "An AMM performance has no beginning or ending. Sounds outside the performance are distinguished from it only by individual sensibility." Or: "Every noise has a note."

"Even so, at this early stage in its development, there are more "normal" instrumental sounds with a conceptual basis in either jazz or classical music than there would be later on. Lou Gare's tenor saxophone wrings out occasional avant-garde peals that wouldn't have sounded too out of place in Sun Ra's band of the period, and Prevost's drumming shares some affinities with the energy players of the day. Similarly, Cornelius Cardew's piano and Lawrence Sheaff's cello sometimes refer to this or that modern classical tradition. But the overall sound of the group, even in 1966, was so different, so idiosyncratic, that it's not at all surprising that both new jazz and contemporary classical audiences were baffled, if not horrified. The experimentation in sonic assault, noise, and chance sound (including transistor radios) would, however, reach the rock fringes (as Prevost points out) in the work of '60s bands like Pink Floyd as well as later industrial groups like Test Dept. and the Jesus and Mary Chain. But the palpable thrill of producing such music at the time is unique to AMM. The group's sonic conception in its totality is so enveloping and comprehensive that, once heard, it becomes impossible to hear music the same way again. Recent devotees of electronica, free improv, industrial, and noise bands owe it to themselves to check out their primary source: AMM."